OHIO’s Dr. John Kopchick is an internationally renowned scientist whose discovery of a growth hormone receptor antagonist in the late 1980s led to a life-saving drug used to treat acromegaly and made him a global leader in the growth hormone field. Photo by Ben Wirtz Siegel, BSVC ’02

OHIO alumnus Rick Hawkins, BSED '75, is a pioneer in the field of drug development who ushered Kopchick’s groundbreaking discovery from the laboratory to the global market—a journey fraught with substantial hurdles. Photo by Pu Ying Huang

Rick Hawkins, BSED ’75, spent the morning of Nov. 2 at Ohio University’s Edison Biotechnology Institute (EBI), hearing about the latest research occurring in Dr. John Kopchick’s lab, where decades earlier a scientific breakthrough put OHIO on the map in the study of obesity, diabetes, cancer and aging.

It was that breakthrough that 30 years ago brought Hawkins, an OHIO alumnus and changemaker in the field of drug development, to Kopchick, a distinguished professor in the Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine’s Department of Biomedical Sciences and Goll-Ohio Eminent Scholar. This dynamic duo would spend the next decade turning Kopchick’s discovery into pegvisomant, known by its brand name Somavert®, a treatment for a rare and life-shortening disease.

“Without Rick Hawkins and a lot of serendipity,” says Kopchick, “Somavert would not exist.”

As Hawkins puts it: “John and I were meant for each other.”

The story behind Somavert is the story of two trailblazers whose work—as individuals and in partnership—has saved lives, advanced science, and generated prestige and record-breaking drug royalties for Ohio University. It’s a story of extraordinary innovation, Bobcat connections and unwavering determination in the face of, at times, seemingly insurmountable hurdles. And it’s a story that continues to unfold.

The discoverer

Kopchick came to Athens in 1987, lured from a position with pharmaceutical giant Merck by an offer to become one of Ohio’s first eminent scholars—an endowed professorship funded by the state and OHIO alumni Milton, AB ’35, and Lawrence, BBA ’66, Goll—and an opportunity to work at EBI.

The institute had one of the few labs in the world capable of producing transgenic animals, whereby cloned genes are transferred from the laboratory to mice through DNA microinjections. It was a revolutionary breakthrough in biomedical research discovered by an OHIO research group led by Professor Thomas Wagner, who in 1981 made global headlines after successfully producing the world’s first transgenic mouse and patenting the technology behind it.

Using transgenic mice, Kopchick began experimenting with growth hormone, a protein that captured his attention because of its ability to dissolve fat while increasing muscle and bone mass, but that also is associated with elevated risk of diabetes and cancer.

“We started out saying, let’s see if we could change the growth hormone molecule in specific places and retain the good things—the ability to make bones grow, decrease fat, build muscle—and do away with any of the bad actions,” he recalls.

Kopchick and the graduate students in his lab began altering each of the protein’s 191 amino acids. The team screened the effects of each alteration by injecting the modified genes into mice, hoping to get a larger mouse resistant to diabetes and cancer. One change made by student Wen Chen, MS ’87, PHD ’91, brought the unexpected: a dwarf or mini-mouse.

“I didn’t believe it, so I had the student go back and repeat the whole thing,” Kopchick says. “Sure enough, he was getting these small animals. One amino acid change made it a growth hormone receptor antagonist.”

Kopchick knew they had stumbled onto something big—an inhibitor, some of the blockbusters of the pharmaceutical industry. Working with OHIO’s Technology Transfer Office, they applied for and received several patents on the discovery.

Students, postdoctoral fellows and investigators in Dr. Kopchick’s lab continue to build on his discovery of a growth hormone receptor antagonist, concentrating on the protein’s effects on growth, cancer, diabetes and aging. Photo by Ben Wirtz Siegel, BSVC ’02

Kopchick began contacting pharmaceutical companies, hoping to license the discovery and develop it into a drug. He zeroed in on its potential uses for the treatment of diabetes, cancer or acromegaly, a rare condition in which the pituitary gland produces too much growth hormone, causing excessive growth of organs and bones and, if untreated, premature death.

“I visited just about all of the major pharmaceutical companies,” Kopchick remembers. “None of them were interested, and I couldn’t believe it.”

His discovery was the first-ever large molecule antagonist, which, in the early stages of development, caused apprehension in the pharmaceutical and scientific communities. Efforts to even get the work published proved challenging—until 1991, when Molecular Endocrinology featured the discovery , aptly illustrated in OHIO’s signature green and white, on the cover of its December issue.

During one of their bi-weekly basketball games and weight-lifting sessions, Kopchick mentioned his struggles to license the discovery to his friend, Joe Dean, BSED ’61, MED ’62, an assistant OHIO football coach. Dean immediately thought of one of his former players: Rick Hawkins.

“Joe told me that Rick is very successful in the drug development business,” Kopchick recalls of that fateful conversation. “I said, ‘That’s exactly what we need. We made the discovery. I know what we have to do to get to the endpoint, but I don’t know how to do it.’”

Dean wrote Hawkins’ phone number on a Post-it®—a piece of paper that wound up in his dirty shorts in the laundry. Kopchick’s wife, Char, discovered it that evening in the washing machine and prompted him to make the call.

The developer

Like Kopchick, Hawkins started his career in the pharmaceutical industry, working for Johnson & Johnson while finishing the final credits for his OHIO degree. He spent 10 years with J&J, learning, he says, “drug development from one of the finest companies on the planet.”

Even in the earliest days of his career, Hawkins’ entrepreneurial mindset began to emerge.

“I used to say: It only takes 12 years and $1.2 billion to get a drug approved. The process is so inefficient,” he recalls.

Hawkins began advocating for making certain aspects of drug development independent of the big pharmaceutical companies—all as a means of expediting the process. In 1981, he set out to do just that.

Using a small bank loan and quickly maxed-out credit cards, Hawkins founded Pharmaco, an Austin, Texas-based company that provided drug development services, like analytical chemistry and clinical trials, to big pharma and established himself as a pioneer in the contract research organization (CRO) sector.

“If you learn how to be successful at one thing and use that as the foundation to whatever you take on next, it can be very powerful and sustaining,” Hawkins says of his career trajectory.

Hawkins’ road to success began as an all-conference high school athlete in Fairfield County, Ohio, where his biology teacher, Max Beougher, BSED ’58, inspired him to study biology in college. Two other OHIO graduates from his community, Milt Taylor, BSCOM ’50, and Mark Wylie, BSED ’49, made those college dreams come true, helping Hawkins secure a full scholarship to play football for the Bobcats after an injury his senior year put that dream in jeopardy.

“I came to Ohio University as an athlete, had to evolve into being a student-athlete and then become a lifelong student in order to be in the business I’ve been in,” says Hawkins. “I learned all of that in Athens, Ohio.”

Hawkins describes his OHIO student experience as “an awakening”—a time to engage in a diverse community and be exposed to new perspectives, and during a tumultuous time on college campuses nationwide . As a defensive back on the Peden Stadium field, he learned the value of teamwork, how trust is paramount to success and that “you better come prepared and bring your best game no matter what.”

He used those experiences and lessons to build a culture at Pharmaco centered on service and saw immediate success, growing the company to more than 2,000 employees. In 1991, Hawkins sold Pharmaco, which later merged with Pharmaceutical Product Development, a global CRO that, in December, was purchased for $17.4 billion.

“The roots of entrepreneurism are different for everyone,” Hawkins says. “For me, it was a combination of being demanding of myself as an athlete and then in business, wanting to be successful and then figuring out what the formula is for that. But it’s also an attitude that you can do it. … To me, a ‘no’ was only a delayed ‘yes.’”

It was just after selling Pharmaco that Hawkins received that phone call from Kopchick, who told him about his discovery and the all the rejections from big pharma and followed up by sending him a proposal. Weeks later, a sleepless night and inquiries from Kopchick prompted Hawkins to start reading.

“I read all night long, and what struck me based on my experience in rare disease drug development at J&J was that this compound should be effective in acromegaly,” Hawkins says. “Within 24 hours, I was on a plane to Athens, and within a month, I had licensed John’s discovery from Ohio University.”

Rick Hawkins’ Nov. 2 return to campus just happened to fall on Dr. John Kopchick’s 70th birthday. They ended the day by attending the OHIO Football game, with Hawkins, a former Bobcat football player himself, pictured here hugging Char Kopchick while (from left) Drs. Joseph Shields, Darlene Berryman and John Kopchick look on. Photo by Rich-Joseph Facun, BSVC ’01

The difficulties

Using proceeds from the sale of Pharmaco, Hawkins began funding further research into Kopchick’s discovery and building a staff to develop what would become Somavert.

In 1994, Hawkins and business partner Chip Scarlett established Sensus Drug Development Corp. Using his drug development knowledge, business acumen and ability to attract investors, Hawkins started pushing Kopchick’s discovery toward the marketplace.

“Drug development is an extremely difficult business, fraught with all kinds of things that can go wrong,” Hawkins says. “With Somavert, there were multiple absolutely daunting barriers to getting this drug approved.”

A growth hormone receptor antagonist was a completely new class of medicines, was being targeted for a rare disease—and was being developed alongside some high-profile failures in protein therapeutics, which made it extremely difficult to raise capital.

“It costs a lot of money to develop any drug, and very few people believed in the rare disease market at the time,” Hawkins says. “I was attempting to raise capital for Sensus under those circumstances.”

Hawkins also found himself having to wheel and deal with other companies.

He negotiated a licensing agreement for technology called pegylation that allowed Kopchick’s compound to slowly filter through the kidneys, extending its half-life. And, with the persuasive help of the founder of the acromegaly patient advocacy group, Hawkins executed another agreement for technology owned by Genentech—one of a few companies producing recombinant human growth hormone or manufacturing large proteins at all—and got the company to agree to produce Kopchick’s compound.

Genentech made enough of the compound to get the drug through its first trials, but the amount of money it wanted to be Sensus’ manufacturing partner for its final trial, and to eventually produce what would become Somavert, was onerous at best.

“I literally was on a plane all over the world trying to find someone to do this,” Hawkins recalls. “There was no one on the planet manufacturing proteins on a contract basis.”

Somavert’s most daunting hurdle was, for Hawkins, an opportunity. Armed with research on all the companies that were developing protein therapeutics—all of which were going to face the same obstacle when it came to manufacturing—he took a business plan to Corning.

Hawkins left Corning with millions to develop a facility that would manufacture recombinant proteins, helping to found what would become Corning Life Sciences Inc. and establishing him, again, as a pioneer—this time in the protein contract manufacturing sector.

Efforts to construct that facility in Ohio and Texas were unsuccessful, but government officials in North Carolina provided Hawkins the land, tax incentives and assistance in securing permits for Covance Biotechnology Services Inc. in Research Triangle Park.

“We pulled that thing out of the ground in the shortest period of time,” Hawkins says. “Not only did they make Somavert—and enough to get it across the finish line—but we got multiple new contracts, FDA inspectors to approve it, and we sold it to Akzo Nobel.”

In 2001, Pharmacia Corp. bought Sensus and was later purchased by Pfizer. In 2003, the FDA approved Somavert for the treatment of acromegaly. Annual worldwide sales of the drug reached $277 million in 2020.

“No one knows this story—how difficult it was and all the challenges we had to overcome,” says Hawkins.

The impact

Hawkins and Kopchick have been celebrating the success of their discovery-turned-drug for the past 20 years. And they have much to celebrate.

Somavert royalty payments, which ended in 2019, have netted OHIO and its inventors $105 million and have been reinvested in the University (see below).

The impact it’s had on Kopchick—named an OHIO Distinguished Professor of Molecular Biology in 2012—can be seen throughout EBI, where the walls are adorned with publications he’s been featured in, places he’s spoken and awards he’s received.

“I’m known worldwide, and I’m a 3 million United miler,” Kopchick says, referring to the number of miles he’s traveled training endocrinologists on the use of Somavert and delivering his “Growth Hormone, Mini Mice, Football, Dirty Shorts and a New Drug” presentation. “Every word in that title,” he says, “was very important for the development and discovery of this drug.”

Among the most notable of Kopchick’s many awards are a 2008 AMVETS Silver Helmet Award, the British Society for Endocrinology’s 2011 Transatlantic Medal and the Endocrine Society’s 2019 Laureate Award for Outstanding Innovation . In 2013, Kopchick was elected president of the Growth Hormone Research Society, and his work and reputation have attracted scholars from around the world to study in his OHIO lab.

“John is a real force in the endocrine drug world,” says Hawkins, who’s seen Kopchick’s students dominate the podium at international endocrinology conferences with their presentations and research. “In his lab, he creates a culture that allows those around him to be successful. That theme has been at the core of my career and why I’ve been successful.”

For all of their success, what means the most to Hawkins and Kopchick is what Somavert has meant to those with acromegaly.

“There’s nothing more humbling than to have a patient sitting in your office, looking at you and saying, ‘Thank you.’ Nothing,” Kopchick says. “It still gives me chills whenever I talk about it.”

For Hawkins, who was awarded OHIO’s Konneker Medal for Commercialization and Entrepreneurship in 2014, bringing Somavert to the marketplace is a full-circle moment—a chance to contribute to the future of a university that paved the way for his future.

“Working with one of the preeminent molecular biologists in the world, at Ohio University, to develop this compound that does so much good for patients and at the same time rewards John and Ohio University in a profound way gives me so much pleasure. I can’t even tell you,” he says.

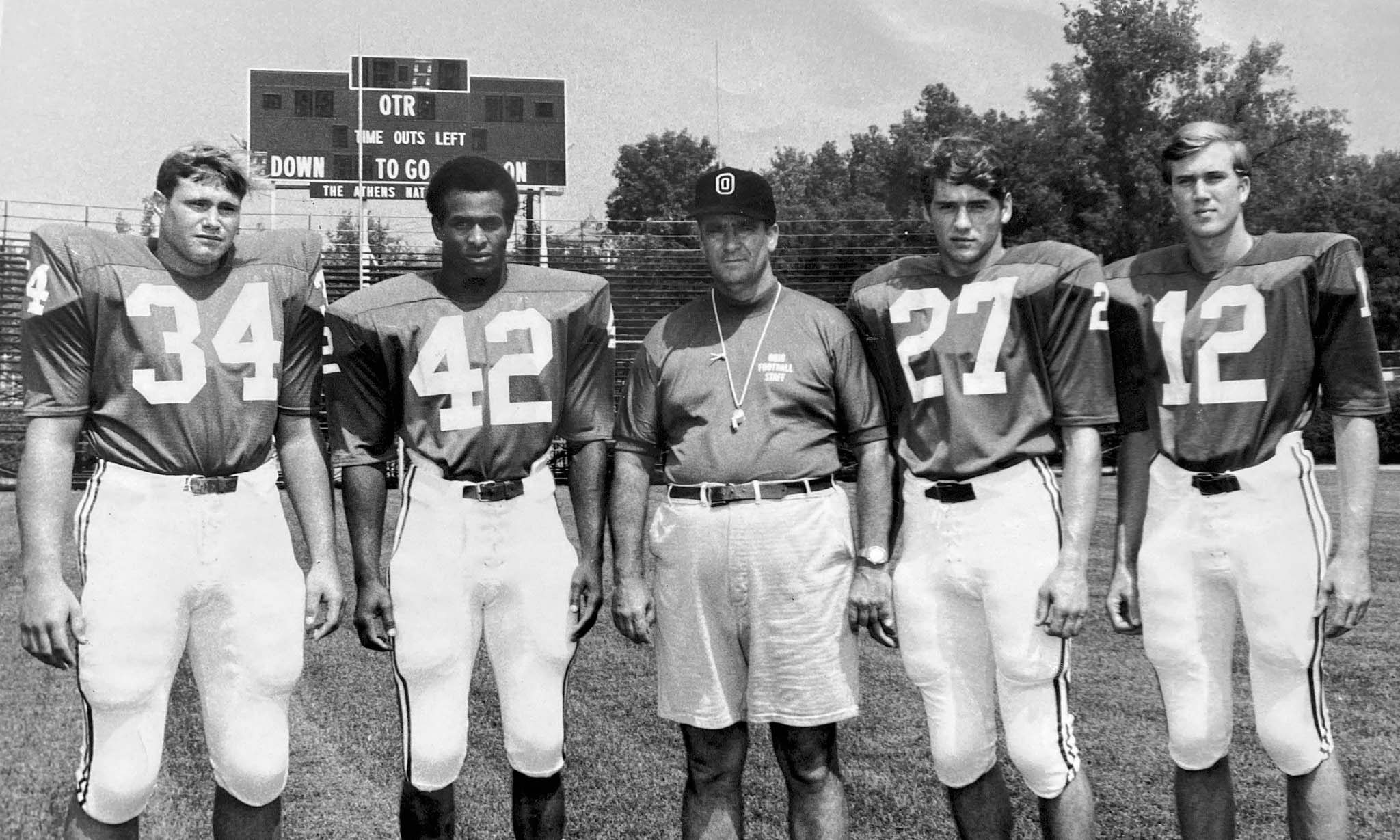

Rick Hawkins (No. 27) was a defensive back for OHIO Football from 1968 to 1972, learning lessons on the field he later applied to his career.

Rick Hawkins’ office tells his life story—from a tractor reminiscent of his rural Ohio upbringing to a drugstore sign. Photo by Pu Ying Huang

Rick Hawkins is pictured with wife Karen at the Oct. 23 OHIO Football game during a 50th reunion he spearheaded for the 1972 football team.

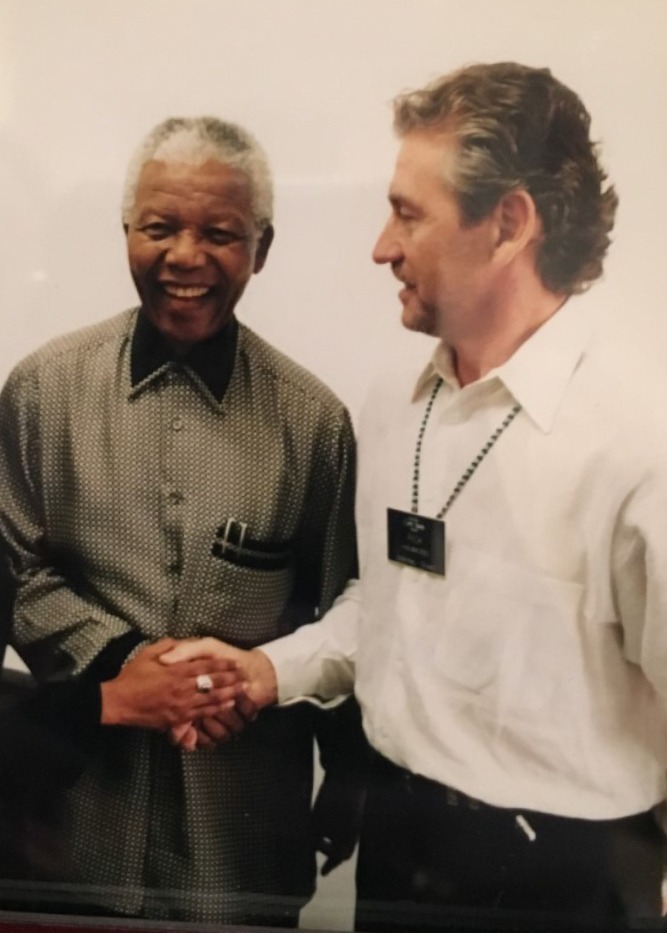

Rick Hawkins’ philanthropy extends to South Africa, where he had a chance to meet with Nobel Peace Prize recipient Nelson Mandela.

Dr. John Kopchick and Rick Hawkins take in student research presentations Nov. 2 at OHIO’s Edison Biotechnology Institute.

Rick Hawkins and Dr. John Kopchick are pictured at the 2019 Endocrine Society meeting held in New Orleans.

The next chapter

Today, Hawkins is CEO and chairman of Lumos Pharma, a biopharmaceutical company developing therapeutics for rare diseases. The company’s latest endeavor? A growth hormone-stimulating drug for the treatment of Pediatric Growth Hormone Deficiency (PGHD). The compound is the opposite of Kopchick’s antagonist but was brought to Hawkins’ attention by Kopchick.

Kopchick learned about the compound from Dr. Michael Thorner, professor emeritus of medicine at the University of Virginia, who contributed to the clinical trials for Somavert and served on Sensus’ advisory board. Like Kopchick with Somavert, Thorner couldn’t find a pharmaceutical company interested in bringing it to market.

“I said, ‘Why don’t you call my buddy, Rick Hawkins?’” Kopchick recalls. “Exactly what Joe Dean told me.”

Hawkins entered a licensing agreement with Thorner, and Lumos Pharma is running a global Phase 2 trial of LUM-201, which, if successful, will allow children with PGHD to take a once-a-day orally administered medication instead of the daily injections of recombinant human growth hormone they’re subjected to now.

Back in Athens, Kopchick and his team of students, postdoctoral fellows and investigators at EBI are continuing their research on growth hormone as it relates to obesity, diabetes, cancer and aging.

Their work over the past 30 years has resulted in significant external research funding for OHIO, particularly, Kopchick says, for aging studies. While working on Kopchick’s growth hormone receptor antagonist, the team also generated a growth hormone receptor “knock-out” mouse, which lived to be nearly five years old and continues to hold the record for the longest-lived laboratory mouse.

Some of the lab’s most promising work right now: “Growth hormone receptor antagonists for cancer,” Kopchick says.

His lab works with a Columbus-based company and has developed an improved version of Kopchick’s growth hormone receptor antagonist that inhibits tumor growth and, when combined with chemotherapy, eradicates certain types of tumors. In December, Kopchick was one of only three university innovators throughout the state invited to share his lab’s work at a special event hosted by Ohio’s lieutenant governor and designed to connect university research with private sector investment.

And Kopchick and Hawkins will take center stage when OHIO hosts the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology’s 2022 Growth Hormone/Prolactin Family in Biology Disease Conference. Slated for May 15-19, the conference will bring clinicians, scientists and industry representatives to Athens to explore the latest developments in their fields—and to hear the story of Somavert.