Off The Beaten Track

Unprecedented career takes Bobcat around the world as a guardian of the rails

Isaac Miller, BSJ '22 | October 7, 2022

Share:

As a first-year Ohio University student, Gary Wolf, BSEE ’71, sat in his mechanical drafting class in the Industrial Technology Building on West Union Street—his attention often captivated by what was occurring outside the classroom: passengers boarding the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad trains at the Athens Depot.

“I sat there looking wistfully out the window, wishing I was on the train and not in the drafting class,” he recalls.

Little did Wolf know that in just a couple years—and before even graduating from OHIO—he would embark on an unprecedented and distinguished career in the rail industry that would take him from the coal mines of West Virginia to the jungles of Colombia and the sands of the Sahara Desert.

Over the course of his 52-year career, Wolf, who resides in Atlanta, has investigated nearly 4,000 train incidents and derailments on six continents. He’s trained 7,000-plus railway professionals on the art of accident prevention and investigation, earned numerous awards for his contributions to the rail industry and served as an expert on train mishaps for the media and in the courts.

But it all started at OHIO and with a professor who opened Wolf’s eyes to a future he never imagined.

Training grounds

Wolf’s OHIO journey began as a high school junior in Columbus, when Kermit Blosser, BSED ’32, a legendary Ohio University student-athlete, coach and now namesake of the Ohio Athletics Hall of Fame, began recruiting him to play basketball for the Bobcats.

It was OHIO Men’s Basketball Head Coach Jim Snyder, BSED ’41, who put Ohio University at the top of Wolf’s college options. A dinner Wolf and his father had with Snyder and then-President Vernon Alden sealed the deal, convincing the high school senior he would be able to balance the rigors of playing basketball with a demanding electrical engineering program.

Wolf’s time at OHIO was marked by the development of many campus buildings, two significant floods and the re-routing of the Hocking River , and the Kent State shootings and subsequent closing of the University in May 1970 . He remembers the 10-15 B&O trains that would roll through campus daily—sometimes stopping and blocking students from accessing buildings on the other side of the tracks—and watching the trains while hiking the grounds of the state mental health center, now known as The Ridges .

“But basketball,” he says, “was the biggest part of my life.”

![Ohio University Men’s Basketball Head Coach Jim Snyder, BSED ’41, poses with the five seniors on his team, including [SECOND FROM LEFT] Gary Wolf, prior to their last game inside the Convocation Center in March 1971. Photo courtesy of the Mahn Center for Archives & Special Collections](https://www.ohio.edu/sites/ohio.edu.news/files/2024-02/Basketball_1971-1-754x1024.jpg)

Ohio University Men’s Basketball Head Coach Jim Snyder, BSED ’41, poses with the five seniors on his team, including [SECOND FROM LEFT] Gary Wolf, prior to their last game inside the Convocation Center in March 1971. Photo courtesy of the Mahn Center for Archives & Special Collections

Wolf lettered in basketball all four years at OHIO. He played in the first-ever game held at OHIO’s Convocation Center on Dec. 3, 1968. He and his teammates secured OHIO trips to the 1969 National Invitation Tournament Quarterfinals and the 1970 NCAA Tournament, as well as a 1970 MAC Championship.

Off the court, Wolf fondly remembers the lessons taught by Professors Emeriti of Engineering Dr. Roger Quisenberry, BSEE ’42, and Harry Hoffee, MS ’51, who “was an excellent lecturer and made the material understandable,” and Professor Emeritus Dr. Clifford Houk, BSED ’55, MED ’56, who “made chemistry come alive.”

Wolf was a “power major” in the electrical engineering program of today’s Russ College of Engineering and Technology. Students in that major were likely bound for careers at power plants or working on transmission lines and generators. But, Professor Emeritus of Electrical Engineering Richard Selleck, BS ’38, BSEE ’48, MS ’51, steered Wolf in another direction.

“He told me after class one day I should consider working for a railroad,” Wolf remembers. “He said, ‘A locomotive is essentially a power plant on wheels.’”

As a child, it was Wolf’s uncle, Ron, who sparked his interest in trains. His uncle was a train enthusiast, whose own desire to work in the rail industry was thwarted by color blindness. According to Wolf, his uncle had Lionel model trains and would take him to the interlocking tower in Loveland, Ohio, where the B&O and Pennsylvania Railroad crossed paths. There, Wolf started learning how to work the tower’s equipment.

“Watching the massive power a train exerts—it started my interest in trains,” Wolf says. “But I didn’t think I’d ever work for a railroad!”

Selleck told Wolf about Southern Railway, describing it as “progressive.” In the summer of 1970, Wolf traveled to Atlanta and interviewed with the Southern Railway System. He was hired immediately into the company’s mechanical engineering program, working there for the next several months.

“That convinced me to make a career in the railroad industry,” he says. “There was just so much you could do in the railroad industry. You could travel all over the place, work on freight cars, work on locomotives—it gave me a lot of opportunities.”

Full steam ahead

Wolf stayed with Southern Railway through graduate school, earning a master’s degree in industrial management from Georgia Tech. In 1975, he was promoted into the operations research group, taking the lead in track-train dynamic studies and train derailment investigations. As part of his research on train accidents, he became a locomotive engineer, qualified to drive trains.

In 1987, Wolf decided to do what hadn’t been done before—start his own engineering consulting firm, Rail Sciences Inc., aimed at helping the rail industry determine the cause of train accidents.

“I wouldn’t call it a privilege, but I have worked on most of the high-profile derailments in the last 30 or something years in the U.S. and Canada,” says Wolf.

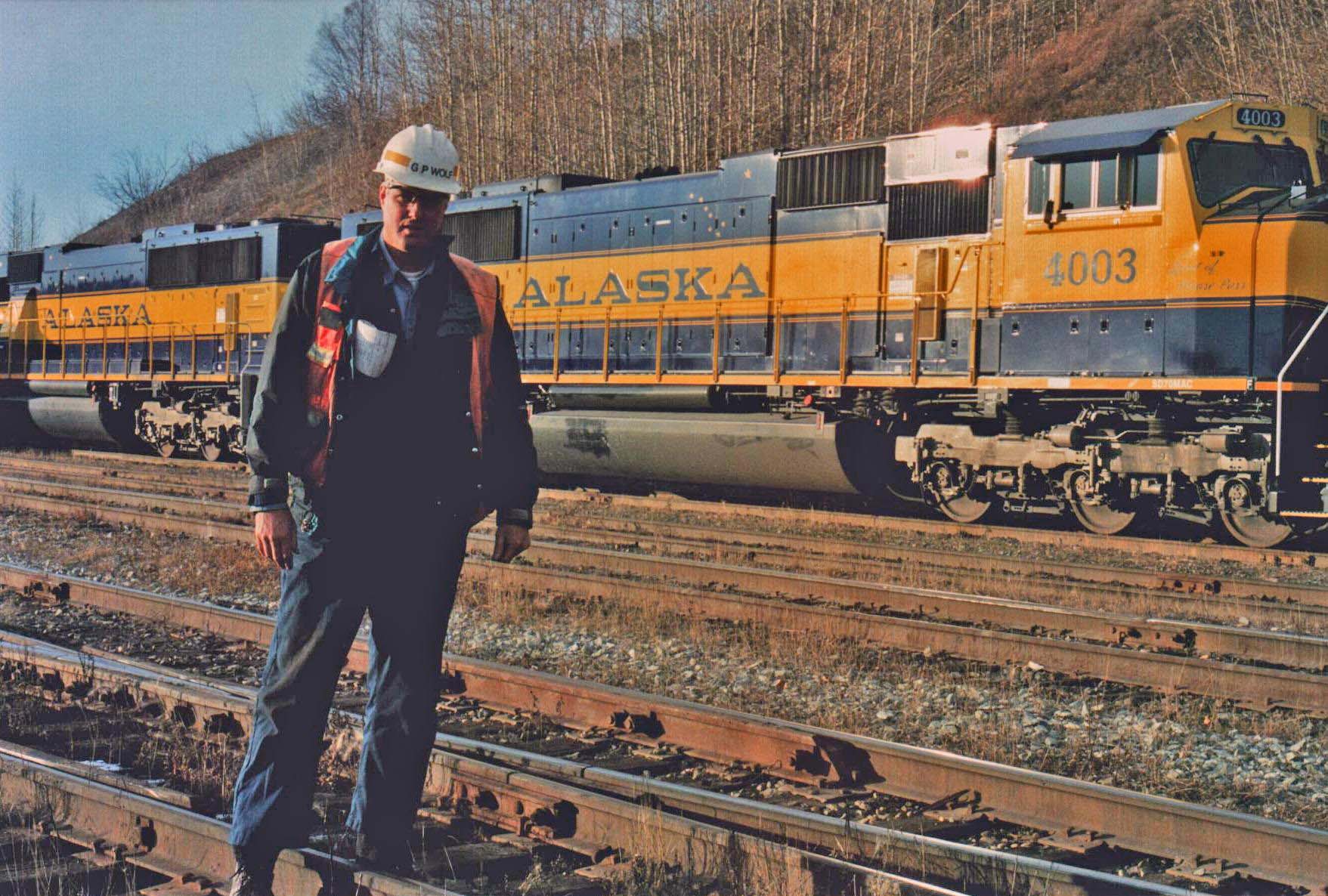

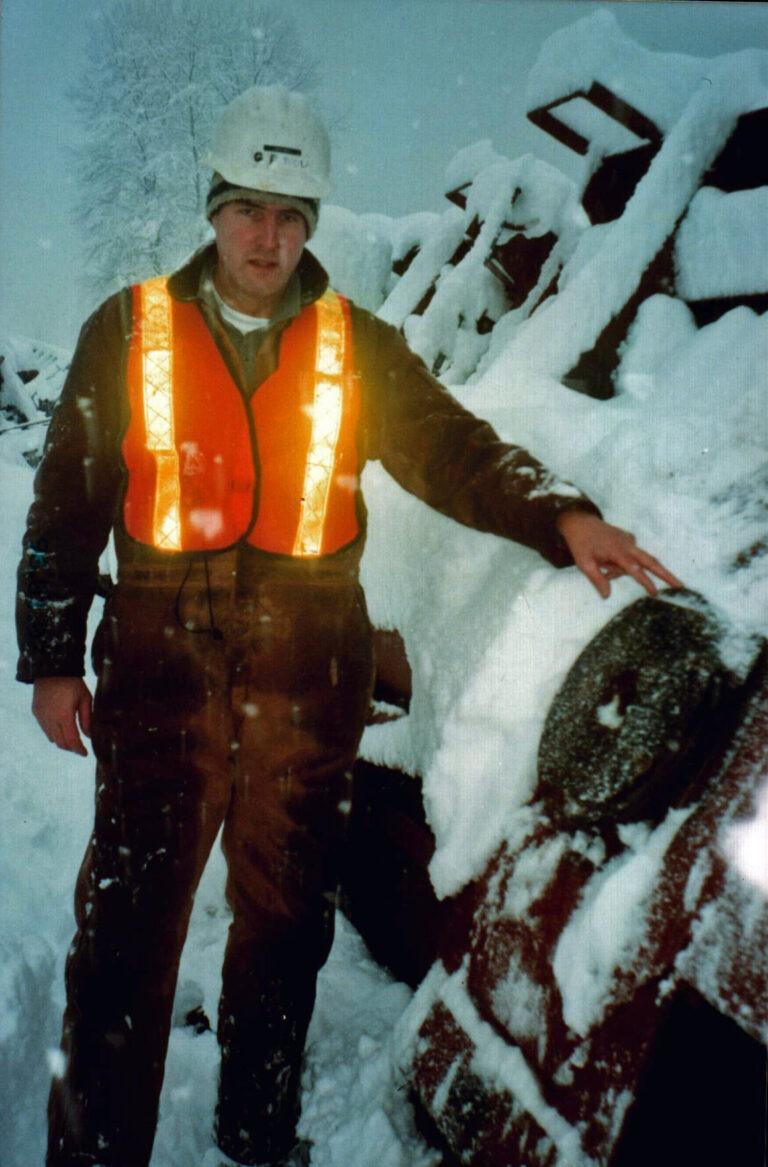

Over the course of his career, Gary Wolf, BSEE ’71, has trained more than 7,000 railway professionals on the art of accident prevention and investigation—work that continues today. In February, he was training the Alaska Railroad on derailment investigation. Photo courtesy of Gary Wolf

He recalls the 1993 Big Bayou Canot rail accident near Mobile, Alabama, where a barge collided with a rail bridge, knocking it out of alignment and causing the train to derail and parts of it to plunge into the water, killing 47 people and injuring more than 100. It remains the deadliest train accident in Amtrak history and the second-deadliest rail disaster in U.S. history.

Then there was the 2013 rail disaster in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, in which an unattended freight train carrying crude oil rolled down track and derailed near the center of town, erupting into flames that destroyed much of the lakeside community and killing 47. Wolf’s work on that tragedy is ongoing as litigation continues.

Wolf’s work in preventing and determining the cause of train accidents not only saved lives but, in some cases, industries and jobs.

In his role at Rail Sciences Inc., Wolf was named project consultant to a double-stack dynamics task force, established by a consortium of railroads and suppliers. Double-stack rail transport, in which railcars are able to carry two shipping containers stacked on top of each other, debuted in the 1980s, followed by several unexplained derailments.

“The shipping industry was threatening to take containers off the double-stack cars if we didn’t figure out what was going on,” Wolf says. “We worked hard for about 18 months, running tests out West. I had to run from Cajon Pass (California) up to St. Louis. We were very successful in eliminating the derailments, which saved the double-stack industry. Where would we be today without double-stack cars?”

Gary Wolf, BSEE ’71, has investigated nearly 4,000 train incidents and derailments on six continents, logging more than 5 million airline miles globally. Photo courtesy of Gary Wolf

Over the course of his career, Wolf has become one the foremost authorities on train accidents and derailments, appearing on news outlets that include CNN and NBC to help explain rail mishaps. In 2017, he was presented the Stephen Marich Annual Lecture Award, given by the Institute of Railway Technology in Melbourne, Australia, to those who have advanced railway industry technical knowledge.

His expertise has taken him from North and South America to Africa and Australia, logging more than 5 million airline miles globally and, at times, working in dangerous situations.

Wolf has conducted work in Colombia several times, but a case in the 1990s was particularly memorable. Because of the ongoing Colombian conflict, he was only allowed to inspect the railroad tracks by helicopter, when suddenly the pilot navigated the aircraft straight up. Once back on the ground, Wolf discovered why: “The guerillas were shooting at us from the jungle, but they couldn’t reach us at 4,000 feet!”

“Derailment work has taken me all around the world and exposed me to a lot of different things,” Wolf says. “I did two different derailments in underground coal mines in West Virginia. I didn’t even know they had railways underground, but they have 15-20 miles of track in some of the mines. And, at six feet, eight inches tall, a coal mine is the last place you want to be.”

In 2010, Wolf sold Rail Sciences Inc., which had grown to 25 staff engineers, two offices and a metallurgical testing lab in Nebraska, to a German engineering firm. He continued working with that firm until 2013, when he founded Wolf Railway Consulting, where he focuses largely on train derailments and dynamics, training those in the rail industry and, occasionally, serving as an expert witness in court cases involving train accidents.

“I’ve trained over 7,000 railway professionals on how to investigate accidents—a lot of FRA [Federal Railroad Administration] inspectors and a lot of NTSB [National Transportation Safety Board] people,” says Wolf.

In 2014, the American Association of Railroad Superintendents bestowed upon Wolf its Lantern Award in honor of the training he had provided to nearly 1,000 of its members over the previous 10 years. And, in March 2021, Wolf published The Complete Field Guide to Modern Derailment Investigation . He’s already sold nearly 2,000 copies to railroad professionals in more than 20 countries.

“I still do three to five derailments a year. I’m trying to retire, and it’s getting harder to travel,” Wolf says. “Climbing around derailments is a young man’s job; I now prefer fishing at my cabin in Montana.”

A four-year member of the Ohio University Men’s Basketball Team that took the Bobcats to the 1970 MAC Championship and NCAA Tournament, Gary Wolf, BSEE ’71, proudly wears his OHIO basketball shirt while visiting Labrador, Canada. Photo courtesy of Gary Wolf

A round-trip journey

As he reflects on his career, Wolf thinks back to his years as a young man—and those spent at Ohio University.

“My academic knowledge, coupled with all the lessons I learned participating at a high level in intercollegiate athletics, provided the solid foundation to propel my career success,” Wolf says. “My time on campus and in athletics taught me about getting along in the real world.”

He laughs a little, recalling what might have been the first train derailment he prevented—back on campus when he was a student. It was shortly after completing his apprenticeship with Southern Railway, and he was on South Green when a B&O train came by. Wolf noticed a “hot box,” an industry term for an overheated axle bearing, and gave a hot box signal to the worker manning the train’s caboose, which resulted in the train being stopped.

“I might have saved a derailment there—who knows,” he says.

Wolf stays connected to his 1970 OHIO MAC Champion teammates, reuniting on campus every 10 years. In 2020, he published The Hay’s in the Barn: A Digital History of Five Magical Years of Ohio University Basketball from 1966 to 1971 “to weave together as many of those memories as possible and leave a lasting legacy to those who follow of what it was like to become a team and stay a team for life.” All of his teammates contributed to the digital-only book.

When his sons were young, he brought them to OHIO summer basketball camps under the leadership of then-Men’s Basketball Head Coach Larry Hunter, BSED ’71, MED ’73, one of Wolf’s former teammates. This summer, he brought his grandsons to the camp, now led by OHIO Men’s Basketball Head Coach Jeff Boals, BS ’95, who was a camp counselor under Hunter when Wolf’s sons attended.

“I’ve been back to Ohio University several times, and it’s still just as beautiful today as it was back then,” Wolf says.

Feature photo: Gary Wolf, BSEE ’71, visits the old Athens train depot—a pleasant distraction for him as an OHIO undergraduate and an unexpected foreshadower of a career like no other. Photo by Ty Wright, BFA ’02, MA ’13