By Allie Stevens, Journalism ‘26, Lizzi Montanti, Journalism ‘26, Anna Parasson , Journalism ‘26, Natalie Davet, Journalism ‘26, for JOUR 4130 Gender, Race, and Class in Journalism and Mass Media with Victoria LaPoe, Spring 2025.

During the spring 2025 semester, the staff of the Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections worked intensively with Victoria La Poe’s JOUR 4130 class, Gender, Race, and Class in Journalism and Mass Media. The students explored, selected, and researched materials from the collections, then worked in small groups to prepare presentations. The students had the option to then expand their research into a blog post like this one for their final project.

College campuses have always been places of discourse and vocal contempt for American policy decisions — and queerness, despite being long misunderstood, has played a significant role in shaping student activism on college campuses. Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, is one such campus where the history of the LGBTQ+ movement on campus reflects higher education’s evolving role and steadfast support of the LGBTQ+ community – challenging stigmas about the queer community, creating inclusive spaces, affirming queer identities and advancing social change both on campus and beyond.

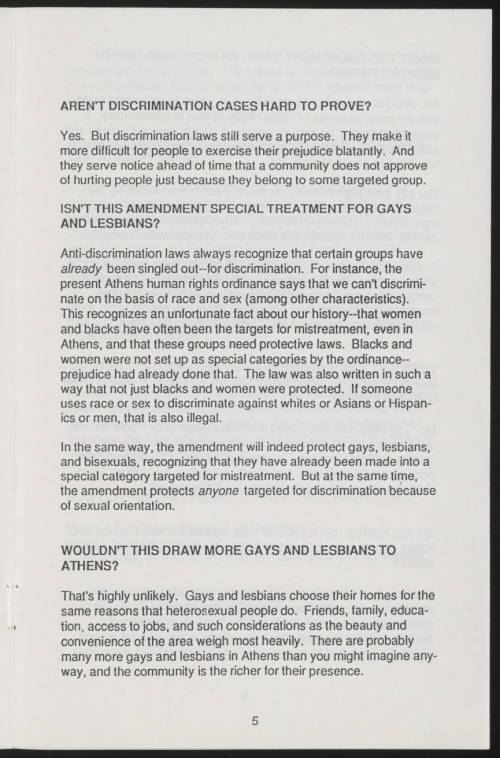

Throughout the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the stigma surrounding the LGBTQ+ community was rampant across the U.S. with universities being no different — but why? The social-learning model is a media theory that suggests that people learn behaviors, attitudes, and outcomes by observing and imitating others. During a time when misinformation was on the rise and social media platforms increasingly allowed public figures to voice their opinions—often without factual grounding—this model becomes especially relevant.

Criminalized and Misunderstood: LGBTQ+ Life Before Acceptance

“ At a time when homosexuals were labeled degenerates and perverts and a moral menace, they used the term homophile to describe themselves… This was a time when homosexual behavior was criminalized throughout the United States, when groups of gay men or lesbians socializing together could be arrested for disorderly or immoral conduct when so called cross dressing was against the law.” (Re-Examining the 1960s, Part One)

The two-step flow theory further explains how such information, particularly when laced with stigmas and misconceptions about queer individuals, travels from the media to opinion leaders.

A contemporary example of this can be found not only in mainstream public leaders such as politicians, but also in the recent phenomena of influencer culture. An influencer is defined as a person who “is able to generate interest in something … by posting about it on social media.” The popularity of influencer content on social media has “incited advertisers to include them as a new marketing communication tool,” and influencers are now seen as “‘opinion leaders’ who disseminate information and shape the opinions of their followers.” Public figures like influencers then legitimize and spread their information, or misinformation, which influences the broader public that follows and trusts them – and often helps solidify these misconceptions into law.

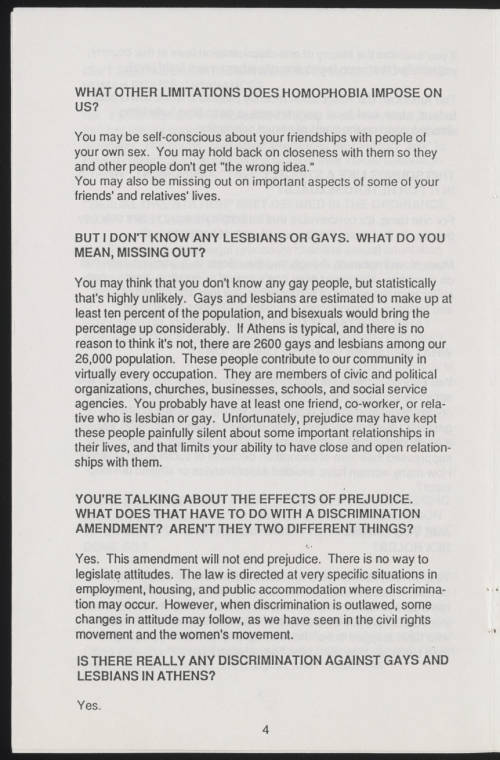

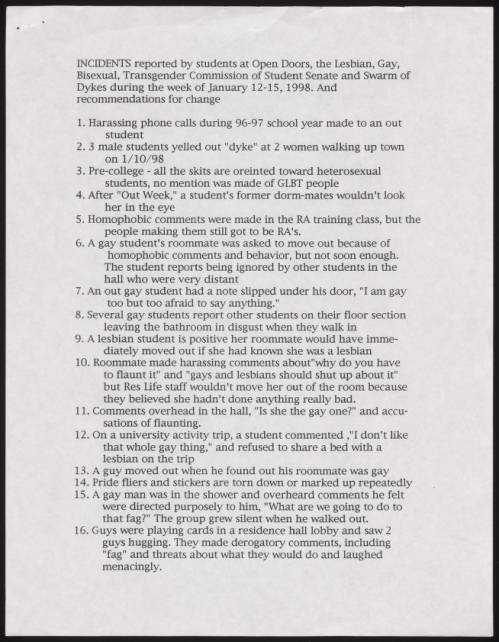

Ohio University, despite having “ a clear and consistent pattern of free speech, free expression, and activism” has not been a stranger to a lack of understanding surrounding the LGBTQ+ community and the subsequent homophobia that often follows. Not only were there documented cases of discrimination against students at Ohio University, but there was also a lack of education and sense of animosity from the town of Athens toward the LGBTQ+ community.

Despite there being tensions both locally and nationally surrounding the topic of homosexuality, the OHIO community is an example that highlights the importance of student activism, staff and faculty support and institutional accountability and reformation. Students, staff, faculty and community members alike all took stands against prejudice and strides toward a safer campus for all.

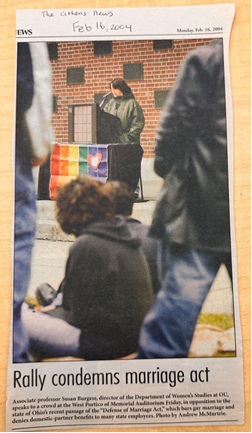

An Ohio University associate professor and director of the Women’s Studies Department addresses a crowd at the West Portico of Memorial Auditorium. The demonstration, held in response to Ohio’s recent passage of the “Defense of Marriage Act,” in 2004, exemplifies faculty activism and solidarity with the LGBTQ+ community during a pivotal moment for civil rights.

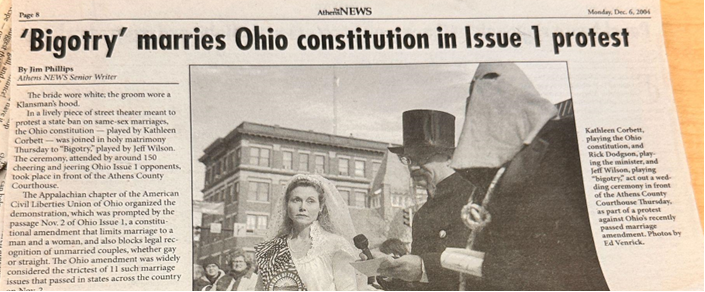

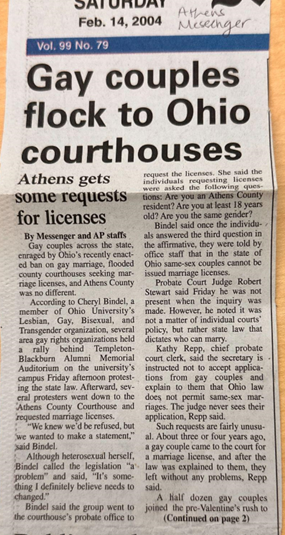

In 2004, as Ohio enacted a ban on same-sex marriage, LGBTQ+ activists in Athens joined a statewide movement of protest. Students and community members rallied behind Templeton-Blackburn Memorial Auditorium before marching to the courthouse to request marriage licenses in defiance of the discriminatory law—an emblem of the OHIO community’s long-standing legacy of queer resistance and student-led activism.

As Mickey Hart , the former LGBT Center director and pivotal member of the LGBTQ+ movement on OHIO’s campus, states,

“I know that for activism, when I was a student, part of it was just trying to make things better and to provide support for folks and to raise awareness or visibility of LGBT people.”

From Protest to Presence: Building LGBTQ+ Visibility at OHIO

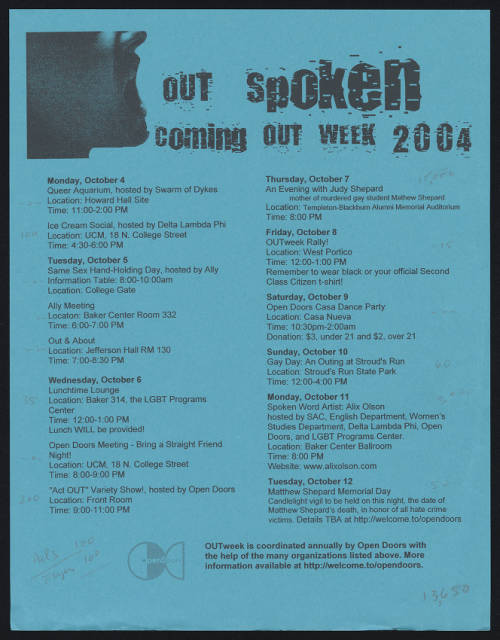

Ohio University’s journey toward LGBTQ+ inclusion is shaped by changing social attitudes and the power of visibility that Mickey Hart so purposefully instituted. Early queer student groups such as the Gay and Lesbian Association (GALA) in the 1980s, later known as Open Doors, and Swarm of Dykes (S.O.D.) in the 1990s, challenged societal norms– creating cognitive dissonance for people accustomed to heteronormative environments.

GALA started in 1972 to create a space for social connection among lesbians, gay men, bisexual individuals, and those exploring their identities. At Ohio University, LGBTQ+ student groups like S.O.D. actively challenged pre-existing heteronormative norms on campus. Their efforts not only disrupted the status quo but also pushed faculty and students to confront and reassess their own beliefs and biases. This activism created a space for increased visibility and dialogue around LGBTQ+ issues.

Additionally, representation has been one of the most powerful tools in shifting pre-existing attitudes . When queer individuals are seen in leadership roles, in classrooms, or through student organizations, it challenges the idea that being LGBTQ+ is something to hide or be ashamed of .

This increased representation helped break the spiral of silence , which means that people began to talk more openly about queer experiences. The more queer voices were seen and heard (through activism and the growth of the Pride Center ) the safer it became for others to speak up. Over time, this helped build a more open and supportive campus culture in Athens.

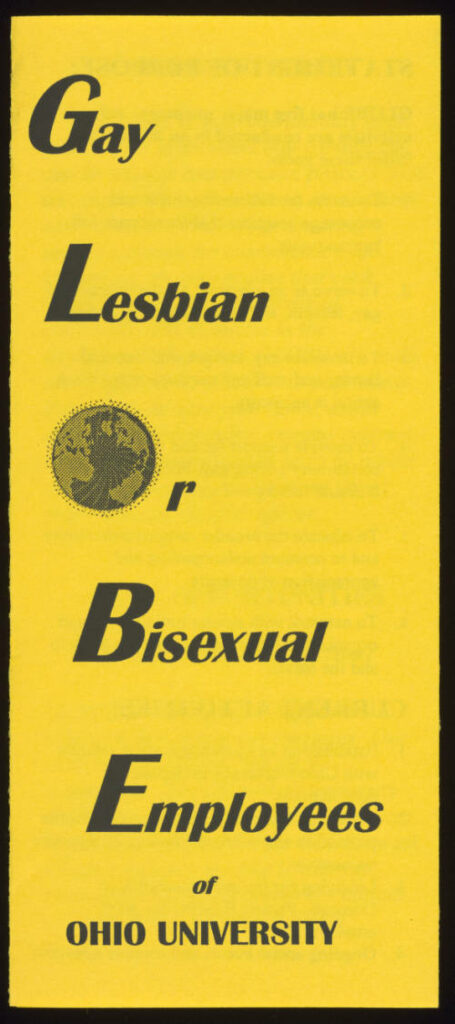

In 1998, Ohio University formed GLOBE (Gay, Lesbian, or Bisexual Employees) to support LGBTQ+ faculty and staff. Its goals were to promote visibility, provide support, and advocate for equal rights and inclusive policies on campus . GLOBE helped lay the groundwork for future progress like the LGBT and Pride Center.

Swarm of Dykes: A Legacy of Student Action

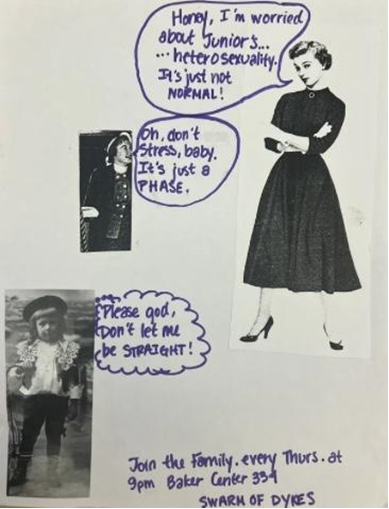

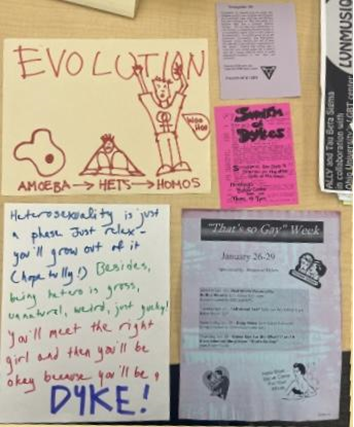

S.O.D. is a student organization founded in 1997 by a group of queer students at Ohio University. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the club fought homophobic stigma on campus and established a community for queer students and students questioning their gender or sexuality.

S.O.D. used posters to reclaim derogatory phrases used by heterosexual students, both as a form of protest and to promote their organization.

Posters featured popular homophobic remarks, such as “It’s just a phase,” “ It’s unnatural,” and “You’ll meet the right person someday.” Except, these remarks were used toward heterosexuals, switching the dynamic, provoking conversation, and challenging pre established agendas.

Rather than promoting their organization in a traditional way, such as simply explaining who they are, what they do, and what time they meet, they used attention-grabbing statements, humor, and visuals.

Victory Early, a fourth year Ohio University student studying Classical Civilizations and first S.O.D. president in over a decade, provides some reasoning as to why the organization takes this approach.

Early states, “We are working to fight stigma on campus about queer and trans communities. We are being visible as well as educating people on the complexities of queerness. We are not a monolith; we are a diverse community.”

This organization’s promotion efforts align with the Entman (1993) outcomes of framing , which are defining problems, diagnosing causes, making moral judgements and suggesting remedies; S.O.D. defined homophobia as a problem and made moral judgements about it.

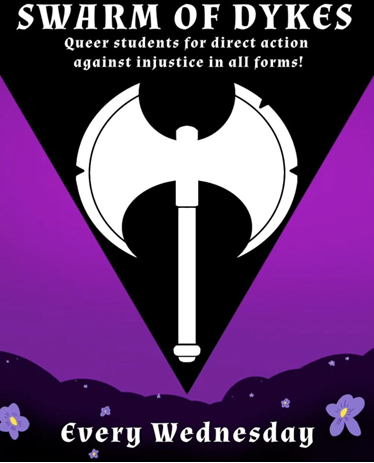

S.O.D. was an active organization through the early 2000s. In the 2024-25 academic year, a group of Ohio University students, including Early, worked to make the club active again.

“I felt there weren’t enough action groups on campus and enough education about the queer community,” Early said.

The re-emerging S.O.D. is also inspired by the original club’s campus activism.

“We hope to follow their legacy,” Early said.

S.O.D. meets every Wednesday at 7 p.m. in Gordy Hall room 213. It is led by a board of executives who are working to make the club more member-run, rather than functioning through hierarchical roles, Early said. All members are invited to regularly attend officer meetings and participate in club planning. Officer meetings are held an hour before regular meetings, at 6 p.m. on Wednesdays on the second floor of Alden Library .

“Our three focuses are community building, education and direct action,” Early said. “We are working to fight stigma on campus about queer and trans communities.”

Throughout the year, S.O.D. hosts activities like art nights, presentations about liberation, skill-sharing PowerPoint nights and distributing harm reduction handouts.

“Our involvement has gone up this [spring 2025] semester with the state of politics and members are excited about our activities,” Early said.

S.O.D. is actively involved in campus protests and demonstrations, specifically regarding Senate Bill 1 (SB1) . On March 28, 2025, Ohio Gov. Mike Dewine signed the bill into law, targeting higher education’s diversity, equity and inclusion and similar initiatives. The bill will cause resources like Ohio University’s Pride Center to lose funding.

The next day, March 29, S.O.D. responded at campus protests, helping host a “funeral for higher education” to display a cardboard graveyard for the Women’s Center, Multi-Cultural Center and Pride Center.

“There are a lot of changes I would like to see at OU. I would like to see an administration that doesn’t just roll over in erasing DEI initiatives. I would like to see a proud OU, an OU that appreciates and utilizes the talents of its queer community. I want to see our ideology spread and other young queers to see hope in their future at a school like OU. With all the oppression of queer and trans people going on right now, we want an OU that does not take our community for granted,” Early said.

Making and Honoring History

At Ohio University, LGBTQ+ history is made every day. The courage and work of previous generations paved the way for today’s generation to be visible and make their voices heard. Over the years, continued student and faculty activism serves as a testimony that queer individuals belong in the OHIO community.

On Founders Day, Feb. 18, 2025, an exhibit called “Out and Proud: The Origin and Evolution of Ohio University’s Pride Movement” opened on the fifth floor of Alden Library. The exhibit highlights LGBTQ+ history at the university from the 1960s to present day through materials from the Ohio University Archives. “Out and Proud” is also available to view digitally .

“We are not just ‘dykes,’ we are the radical, the oppressed, your sisters and daughters who have gone unheard our entire lives. We just want our voices heard.” – Victory Early, President of SOD.

Limitations

There were a few limitations that we discovered while compiling our research, and those included:

- Archival gaps: Some LGBTQ+ history at OHIO may not have been documented or preserved in the archives, so informal activism (especially from marginalized subgroups we might not be aware of) might be underrepresented.

- Intersectionality: There were some slight limitations in fully capturing the layered experiences of the LGBTQ+ individuals who are also BIPOC, disabled, low-income, or religious → most of the archival evidence having to deal with activism for queer folks has to do with specifically gay, lesbian, bisexual and sometimes trans students on campus.

- Temporal scope: Covering such a broad time span (1960s to 2025) may limit the depth with which any single moment or decade is explored. This could possibly lead to an uneven representation of the movements on OHIO’s campus over time, particularly where archival source availability is imbalanced.

- Researcher Positionality: Our own identities, experiences, and proximity to this subject matter played a role in shaping what we noticed or prioritized in our work. While this can offer depth and perspective, it can also introduce subjectivity.

Future Research

There are two main ways we would continue our research about LGBTQ+ history at Ohio University.

To expand our findings on student activism, we would research and feature more student organizations in addition to S.O.D. We could connect with alumni who were involved in past student action groups to learn more about their personal experiences.

Also, we find it timely and important to further research the future implications of SB1 on LGBTQ+ initiatives at Ohio University. We could develop a timeline of SB1 developments at the university and seek perspectives from current Pride Center staff.

External sources:

- Swarm of Dykes Instagram. @swarmofdykes

- Serge, Lauren. (2021). “Swarm of Dykes: Swarm of Dykes’ activism influenced LGBTQ+ resources today.” The Post Athens. https://projects.thepostathens.com/SpecialProjects/swarm-of-dykes-lgbtq-queer-ohio-university-activism-lgbt-center/

- Balmert, Jessie. (2025). “Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine signs higher ed bill that eliminates DEI, bans faculty strikes.” The Columbus Dispatch. https://www.dispatch.com/story/news/politics/2025/03/28/dewine-signs-higher-ed-bill-that-eliminates-dei-bans-faculty-strikes/82688476007/

- Gordy Hall, Ohio University website. https://www.ohio.edu/building-directory/gordy-hall

- Alden Library, Ohio University website. https://www.ohio.edu/building-directory/alden-library

- Pride Center, Ohio University website. https://www.ohio.edu/diversity/pride-center

- Scotto, Gabriel. (2025). “‘Out and Proud’ tells the story of the LGBTQ+ community at Ohio University.” The Athens NEWS. https://www.athensnews.com/news/out-and-proud-tells-the-story-of-the-lgbtq-community-at-ohio-university/article_06ded61b-63d2-495f-bbbc-eef419f00db5.html

- “Out and Proud” digital archive. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/e25b963c1d65439c850aa37d154d92ef