Ohio Today asked Russell and Galvano to unpack each element that makes up Lacuna and to explore the complex relationships reflected in the work. A virtual gallery of Lacuna and excerpts from both in-person and email interviews follow.

...

Ohio Today : Let’s start by talking about the name of the work. Why Lacuna ?

Galvano: I was attracted to the word Lacuna because it is unfamiliar and evocative. I felt there was some relationship to the piece we were making but I wasn’t sure at first what that relationship was. I liked the word because it seemed to give the piece room to grow.

OT: Does Lacuna have a meaning or a translation?

Galvano: Lacuna is a gap. Something is missing. The word is often used in the context of literary translation, when part of a text is missing. In the dictionary, it’s a medical term used to describe a gap in the bone.

What's interesting about Lacuna is the idea of absences or a gap, the mystery of something that's gone. The attitude of that word fits with the general content that both David and I work with in our individual research practices. Lacuna evokes a sense of intellectual mystery, but also this idea of absence. What's great about any absence is that we can then search for that missing one. Or we could go into those empty spaces and try to find something. So that was the impetus for using that word. As we built the piece, we referred back to that.

OT: David, what are your thoughts on Lacuna ’s origin story?

Russell: The title, like Mateo said, evolved because this piece we put together combines various bodies of work that we have been generating. And one of the bodies of work included drawings I did for a project called The In-between, which also references void spaces . And so, we were trying to keep with the spirit of that. But we wanted the piece to have a stand-alone title. So, we had to figure out what that would be. That's where Lacuna came from.

OT: Explain the elements that make up Lacuna .

Russell: The Breaths were a series of drawings that I started in the sketchbook, I don't know, 10 years ago maybe. And they were meditative drawings where I would simply breathe and then just start drawing without planning. I created some interesting things in the sketch book. Then I transferred those to larger pieces of higher quality paper and developed them further. But the process was still the same. They were just larger, a more committed idea. From the beginning I was interested in their potential--because I do a lot of sculptural craft work and so forth--they have an ethereal, wispy quality to them. And I was intrigued by trying to explore them in three dimensions. How could I make these wispy, ethereal things in three dimensions and retain that kind of spirit to them?

I've always been part designer, part maker, part explorer, because I love designing, creating from just the idea and building a world. But also, I like the specifics of crafting and creating something sculptural. The sketches became the design, the basis for the sculptures. My next step, of course, was to bring them into more of a reality--out of the two-dimensional realm into the three-dimensional realm. So that's just a process that I continually engage in, in my theatrical practice. I do drafting that then becomes three dimensional models that then become full scale stage sets. Same thing in costumes. They're costume sketches that are created into a real garment or hat or a mask or something worn by an actor. So that is a process that I am accustomed to--going back and forth.

OT: And this one just became something that you wanted just for yourself?

Russell:

Right.

OT:

Can you talk about that distinction between what you create for work and what you create for yourself?

Russell: I do technically rigorous, mathematically accurate drawings that I have to deliver to somebody and they have to build from its guidance and it must fit and function effectively. To balance that, I need some time to clear my thoughts, and to replenish the well. I draw upon a meditative approach in my personal work. It helps reset my brain in some way that is appealing to me.

Galvano: I like the way that you're describing the process of translation from the sketch to the model. That translation allows for breakthroughs because of things that are lost and found in the process.

We each reference metaphors to the inner life or to meditative states. I think that’s a touchstone for us in our work. With Lacuna , the unfolding pace of the sound and imagery creates a sense of openness to the unknown and reverence in the space.

OT: David, tell us about the animated stick figure that is part of Lacuna .

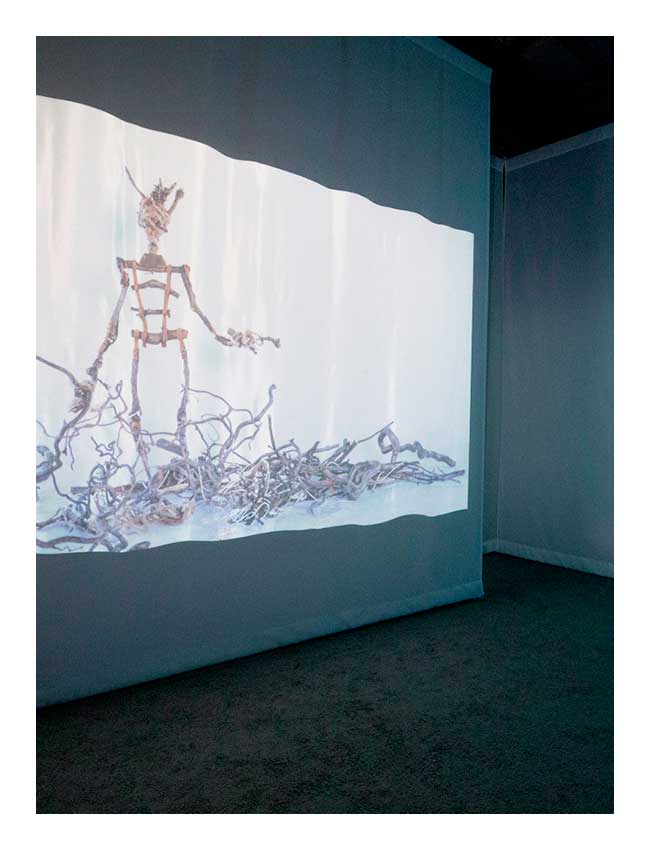

Russell: I created a puppet at the New England Puppet Intensive, a 12-inch figure created out of sticks and scraps of leather, and twine and wire. That was a completely articulate figure that we used in some of the training there. After the residency, I wanted to see if the puppet could have more of a life. And I could have chosen to perform that live, but Mateo and I were charged with creating a new media kind of a work when we were invited to mount a piece at Currents New Media.

So, I thought of stop motion. The kind of articulation I was interested in would take multiple people and lots of rehearsal and so forth. I wanted to see if I could create that in a stop motion studio experience, which I had never explored before. So, I did what I call stop motion puppetry.

OT: Tell us how all the pieces of Lacuna came together.

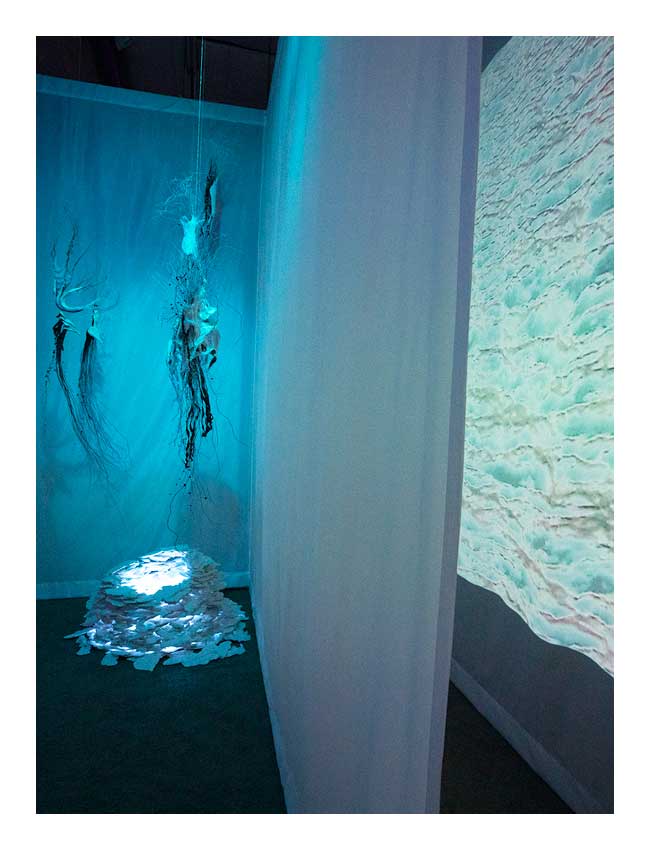

Russell: We created this room made of silk. It is the white void that surrounds and develops the piece, which you walk through. We intentionally set up two entrance/exit points so that the viewer could wander in and out of the installation from either direction.

There were the Breath sculptures, the structure itself (the white silk room), the stop-motion films, and the sound. In addition, we created a three-dimensional cast plaster leaf well. There was light at the bottom of that well. The Breath sculptures were gathered around the well. This was yet another light source in the room, coming from the ground instead of from above.

Galvano: When we look into the well--and this had a nice effect at the festival--it gives the sense that we’re looking down, but what we are seeing is the sky…as if we drilled a hole through the earth and could see the sky out the other end. That was my fantasy about it. Developing the leaf well was an interesting part of this collaboration, because we wanted to have this area where the Breaths sculptures could be congregating. We had to figure out what we would use for their focal point.

OT: Sort of like an anchor?

Galvano: Yeah. It was something that was rooted down in that room. Another light source was the film of the bramble puppet which was so visually captivating.

Russell: This bramble puppet was an interesting combination of ancient and contemporary modes of craft. It has sort of the skeletal nature to it. The breath sculptures don't really have an identifiable skeletal form. But they do have what I call a pre-emergence kind of form.

Galvano: David and I probably had different experiences of elements in the work. I was thinking of the hanging sculptures as the ‘ancient ones,’ or something. And then the bramble puppet is perhaps a younger being trying to find its way and to do something, make something happen.

OT: The bramble being: Does it have a story?

Galvano: I think there's a thousand stories.

Russell: Right. There's a narrative track. There is a beginning—so an emergence—and then a dissolving. So that happens and the 8- minute film loops continually. But this puppet does go on a journey. It does some basic movements of first just coming together, establishing its form and its language of movements. It figures out it can walk and do other things. Then it makes discoveries. It gathers flowers and plants them from underneath the ground, pokes them up through the surface; it gains a purpose.

But, then it's very open to interpretation regarding the meaning. To me, it's metaphorical. Some people were very sad; some people even thought there was violence in it. So, there are lots of different interpretations. I think, once again, when we come to a piece and observe something, we bring whatever we bring, and it's reflected back in the work.

Galvano: We did get that question…people would say, well, oh, it's so interesting… what does it mean? And I often turn that back on people. I say; well, what does it mean to you? Some are happy for the invitation to have authority over what their experience is going to be. Others want to know more from the artist. By discussing different elements of the piece, such as the technical approaches, or the way that we collaborated, it often fleshes out further meaning for the viewer.

Russell: There is a mystery that is overarching in the piece, and in life in general. I'm okay with the idea there are things that we just don't know…life itself is actually just a mystery.

OT: In the stop motion puppetry piece, the bramble being pushes flowers up through the ground from below. Then there are the Breaths that look down from above. Is there a relationship between those actions?

Russell: That's a reflection of what we do, and how we are awake, and then we sleep. We're in this state of hyper consciousness and then we can drop into the subconscious realm. And that's just as basic as night and day. So, it's just sort of a flip flopping that's happening all the time.

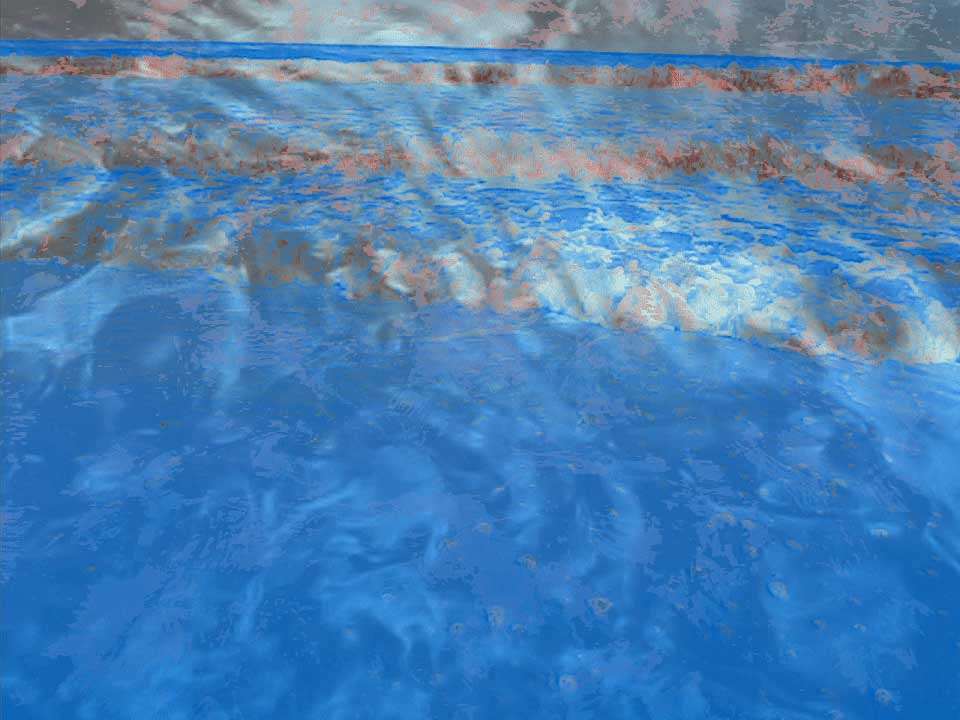

OT: Let’s talk about the water film element to Lacuna .

Galvano: The film is projected on the outside of the big silk room. It has the viewer ask, “Where am I? Where am I situated? Am I above the clouds or am I below the bottom of the ocean?”

We're looking at layers of superimposed elements of clouds and layers of water. We’re able to look through the clouds to see the bottom of the ocean and vice versa. So that creates an atmosphere that suggests we're allowed as viewers to go to all these different places. We don't have to only just stay on the surface of the land. We can go into the water, we could go under it, we could go above the clouds. And this is what happens with the bramble puppet. It also does that--it has access into these different places. It does it in a way that is very like a human, because the puppet is not fully aware of its authority or power. I think that it is on an expedition or a quest for understanding. And I think that reflects the experience of the viewer exploring the world of the artwork.

OT: Mateo, let’s turn to the sound scape you created for Lacuna . What were your thoughts when you created this element?

Galvano: I have a background in singing experimental vocal and classical choral music. I've been composing recorded audio works that layer my own improvised wordless chanting. Sometimes it's based in poetry that I write. I flip it so that we're hearing it backwards or alter the audio information in other ways. For Lacuna , I changed the vocal pitch in search of a genderless or ageless sound.

There's also drumming that I created digitally, and I merged these things together using digital software. It sounds like a procession in some other land. They've got some drums and they're walking along and it's at a certain kind of a slow-ish pace. This is what I visualize when I think about this piece of music.

OT: When you were creating this, were you thinking about how it would relate to the other aspects of Lacuna ?

Galvano: Yes. I wanted it to be a soundscape that the bramble puppet could work with. The bramble puppet is at the crux of the work. The sound was needed to create a kind of a pulse in the work, without interrupting the puppet’s journey. The sound touches every aspect of the piece. As you're in the installation, and as you approach, you can hear it softly. I think it has a way of tying invisible webs around the different elements. The soundscape helps to unify the piece.

OT: In the end, what is Lacuna to each of you, and what did people tell you it was to them?

Russell: So, we drove out to Santa Fe, which is a 24-hour drive.

Galvano: Three days of driving.

Russell: We had a lot of time to think about and process the work. This whole piece is our own version of a creation myth. But once again, I don't want it to just end there. I want it to be broader and still have the mysterious edge to it as well.

Somebody said it sort of made her sad. That there was this aloneness of the figure trying to create something.

OT: So instead of a creation story, for her, it was sort of like an ending story?

Russell: No, I think just a story about a yearning and a searching…of isolation maybe, a figure just striving to create something. To me, it sounds positive.

Galvano: Somebody said that the creature needed some basic things. It needed to learn how to walk...there was so much effort. I thought that is so interesting that this person said this.

OT: They were troubled by how much effort it took?

Galvano: No, they weren't really troubled. I think they related to that human condition…We're born and we have to learn all this stuff. We have to try to be , we have to try to become something. I thought that was so interesting because of how it was difficult for that creature to walk. In order for him to walk, it meant that David spent many hours re-clipping the string that lifted the knee, just the right way, and shooting another frame…and another.

OT: Lacuna represents your first definitive collaborative art project. How has it informed your relationship?

Galvano: We advise each other in different ways, and we influence each other a lot. But Lacuna was a clear decision we made to produce a multi-media artwork for Currents New Media. There were different things that we both were able to bring to this collaboration from distinct research practices. We merged them together, and it really worked.

Russell: We wanted to make sure it was still a creative process during the installation phase, and keep it open to whatever it wanted to become. Luckily, our planning worked better than expected. So that was a great bonus, but we were perfectly willing to change it if we needed to, or to abandon something.

Galvano: Because we have strengths in different realms--David has a sense of the theatrical that's very different from mine--we kept checking in with each other. Everything that would enter into the piece had to be approved somewhat by the other, which helped to bring about thoughtful decisions.

After the festival, we had to cast Lacuna aside for a few months so that we could turn our mind to other things. We each have solo projects and commitments to fulfill. But I have a feeling this piece is going to continue to inform us in our practice. Lately we have begun to investigate exhibition venues in which to reiterate the work and continue the collaboration.

Galvano, BFA ’09, MFA ‘14, CERT ’15, is the recruitment and retention liaison and a lecturer in Foundations in the School of Art + Design. He is a multidisciplinary artist whose work includes visual art, creative writing, and sound compositions. Russell, BFA ’93, is associate professor of Scenic Design and head of Production Design and Technology in the School of Theater. Russell is a costume and scenic designer, a props technologist, and a visual artist.