Southeast Ohio is currently in the midst of the most severe drought in the area in recent history. The Appalachian Ohio region is typically wet and lush well into fall, but the unprecedentedly dry conditions are impacting forests and farms—killing established trees and wilting crops. The drought is so severe that the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) designated much of southeast Ohio as a natural disaster area on Sept. 4, 2024.

As farmers and others who rely on the land for their livelihoods attempt to recover, ecosystem ecology experts like Dr. Jared DeForest are working to study the drought and potentially apply the results to other ecosystems that aren’t usually prone to drought. Largely, what his research program is working on is trying to create a link between soil, microbes and plants and trees.

Dr. DeForest is a professor of environmental and plant biology in Ohio University’s College of Arts and Sciences and has been leading a forest soil manipulation experiment for more than 15 years. In the experiment, soil at three research sites is divided into three sections and exposed to four different treatments (lime, phosphorus, lime and phosphorus together and an untreated control). The experiment was originally set up to understand the consequences of coal-fired production on how ecosystems function, but that data is now being used to measure the impact of the drought.

“Basically [coal-fired production] is acidifying soils and the experiment is essentially adding nutrients to the soils, mostly nitrogen,” said DeForest. “So, what I did is I added lime to the soils to basically neutralize a lot of the acidity to make them more nutrient rich—this is all a fertility thing. I wanted to get crummy, poor soils and make them nutrient rich. And then I added phosphorus. I was very curious in understanding how phosphorus as a nutrient, impacts how forests behave.”

The experiments proved that DeForest’s treatments led to an overall increase in soil fertility. The cycling of all nutrients increased, including essential nitrogen and phosphorus.

DeForest is now leveraging his existing experiment to study the impact of soil manipulation on the recent drought. Besides a relatively dry year in 2012, he says that since starting the experiment the results have been largely consistent—there has been plenty of moisture in the soil to sustain plants and trees and the microbial organisms they rely on.

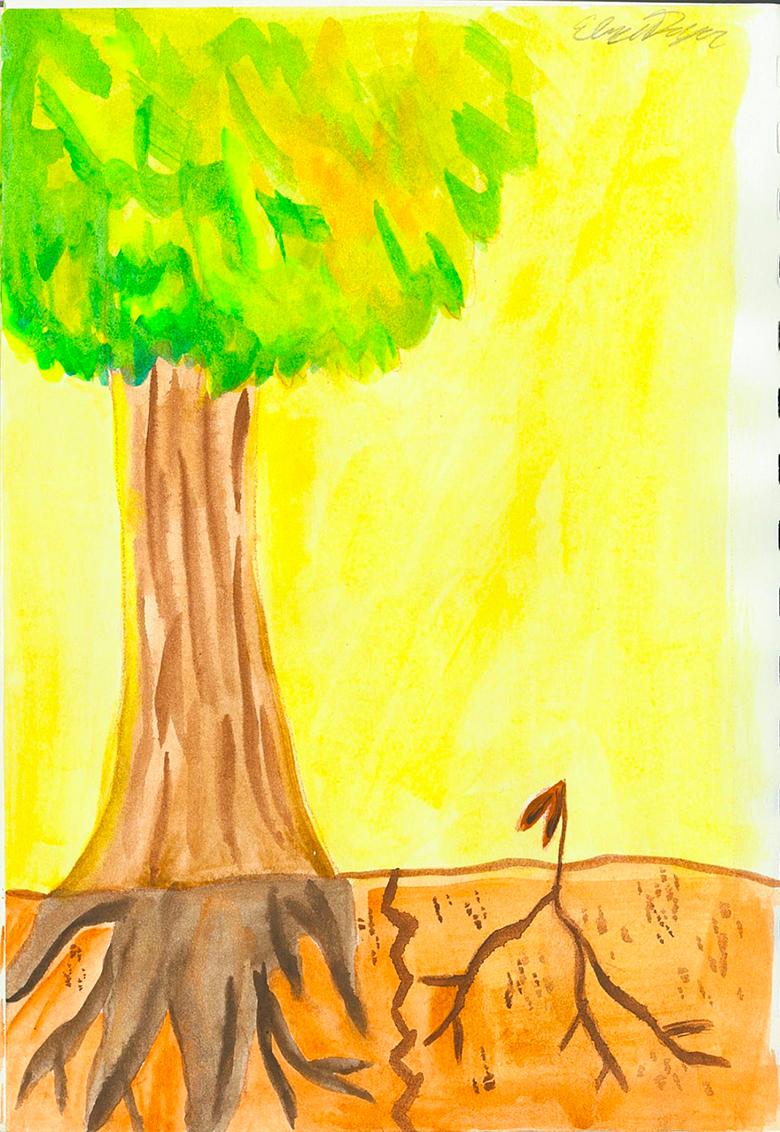

This year, DeForest has anecdotally observed a lot of dead trees, especially in the understory and midstory—the smaller, younger trees in the forest—due to the lack of available water. Trees that didn’t die had leaves that were changing color and falling much earlier than usual, with some species going dormant more than a month early.

“What I'm really interested in now is how does this change in soil chemistry mitigate or make trees more susceptible to drought,” explained DeForest. “It's one thing to say, ‘oh, we had a drought and a whole bunch of trees died.’ Okay, yeah, whatever. But if we can say, ‘yeah trees died, but it was more confined to the nutrient rich sites than the control,’ then that’s valuable information.”

OHIO Environmental and Plant Biology Professor Dr. Rebecca Snell often collaborates with Dr. DeForest on research and says incorporating the drought into the study adds a natural variable.

“It's called a natural experiment,” said Snell. “Which is basically we didn't plan for it, we could never have planned for it, it just happens, and when it happens you take advantage of it.”

Student involvement

When gathering samples for his research, DeForest and his students collect soil from 36 plots spread over the three sites. At least 12 to 15 soil cores are taken from the soil’s surface at each plot. Together, students and faculty then sieve and homogenize the soils to prepare them for analysis. It is very important the same process DeForest used when starting the experiment is repeated to avoid unintentionally skewing results.

“Because I'm doing long term data, it's almost a ritual of what I do to keep things consistent,” said DeForest. “I tell students, what I did back in 2010, the same methods I’m using today—even though I have better ways of doing it, I can’t change it.”

After collecting the samples, students test the soil’s moisture content, acidity, nitrogen, phosphorus and enzymes that act as biomarkers.

Kate Richards is a senior at Ohio University studying environmental science who works in DeForest’s lab as a Program to Aid Career Exploration (PACE) student. Richards started as a PACE student this past summer when DeForest decided to begin comparing past results from his experiment to samples taken during the drought.

“Since I’m an environmental science major, not a plant biology major this is all kind of new to me, so a lot of it is a learning experience, but usually, my job is to do the hands-on science and clean up,” Richards said. “We’re basically doing the same exact thing he's been doing for the past 15 years, we just did it again to see how it would compare to the data we got [during the drought].”

Measuring the extent of the impact caused by the drought is still a work in progress, but Richards says the results so far have shown a large impact.

“We just have one small step left and to analyze all the data but comparing it to the numbers that I worked with over the summer, you can just tell that the drought has killed any living microbes or organisms in the soil and have completely affected nutrient availability.”

Applying results in southeast Ohio and beyond

The drought is very localized which means the impact is limited to southeast Ohio and some surrounding areas, however, southeast Ohio is not an area typically prone to drought, and especially not droughts of this magnitude.

“I think that's the thing with climate change is areas that typically don't get drought are going to get droughts,” said Dr. Rebecca Snell. “And so, we've got a problem of places that typically are wet, are now experiencing droughts that they don't normally get. I think it's applicable in that way if we're looking at particularly wet areas that are now suddenly dry, what can we expect—do these areas have any inherent resilience to this.”

The mixed mesophytic forests of the region are not well adapted to this severe lack of moisture and that may impact the flora and fauna. Snell says that southeast Ohio is home to a surprising amount of biodiversity which also makes studying this drought unique, but important species could be threatened if it were to continue.

“We actually have one the highest regions of biodiversity in temperate forests. We have species here that, typically, you find much further north and we also have species that you would find as you go further south and they kind of mix here,” Snell said. “I’d be scared [if a drought were to continue]. I think with one year [of drought] we’ll see recovery. I’d be terrified if we have a multiple-year drought.”

DeForest sees potential in using results from the soil experiments and applying those results to other ecosystems that typically don’t get drought. If a particular soil treatment is successful at making a plant drought resilient in Appalachia, it may be able to be applied to other similar ecosystems.

“When we have climate modelers trying to understand drought and moisture and how it affects ecosystem function and carbon sequestration that’s where I see value in this,” he said. “This could apply to other areas that don't really get drought.”