By Morganna Marks, senior History major and OhioLink Luminaries intern, 2022-2023

As the Ohio University Libraries OhioLINK Luminaries intern for 2022-2023, I knew from the beginning that I wanted to create an exhibit. I wanted to do something very different from what I do in class. As a history major, I write a great many papers, and I wanted to push myself to do something new. I also wanted to showcase the collections of the library in some way, which an exhibit would do beautifully.

I just had to pick a topic. The idea of Plants and Printing grew out of my love of gardening and my interest in medieval herbals. It was expanded when I realized the extent of the library’s collection when it came to botanical art. As I researched the art form, I fell in love with this scientific and artistic niche. Here was a gorgeous art form, with a very long history, in service to the transmission of knowledge.

I began my research process the way I start any research process, by diving into ALICE (Ohio University Libraries’ database of books in the collection) and searching the stacks at Alden Library for anything related to the topic I’m digging into. I found an excellent reference in the form of The Art of Botanical Illustration by Wilfrid Blunt, with the assistance of William T. Stearn. This book built a framework of understanding for me to go forward with my research. I also availed myself of a few websites, like https://www.huntbotanical.org/ and https://www.botanicalartandartists.com/ , two sites that are rich in information about botanical art. Many thanks to Dr. Miriam Intrator, Special Collections Librarian and my supervisor during my time at the Mahn Center, for tipping me off about the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation!

From these seeds, my research grew as I tracked down information about the artists and writers named in these sources. Paired with this exploration into modern sources, was my digging into the Mahn Centers’ Rare Books and Special Collections . I started with the Gilbert and Ursula Farfel Collection of Incunable and Manuscript Leaves , and then branched out into the rare book vault, which has become my favorite room on Ohio University’s campus.

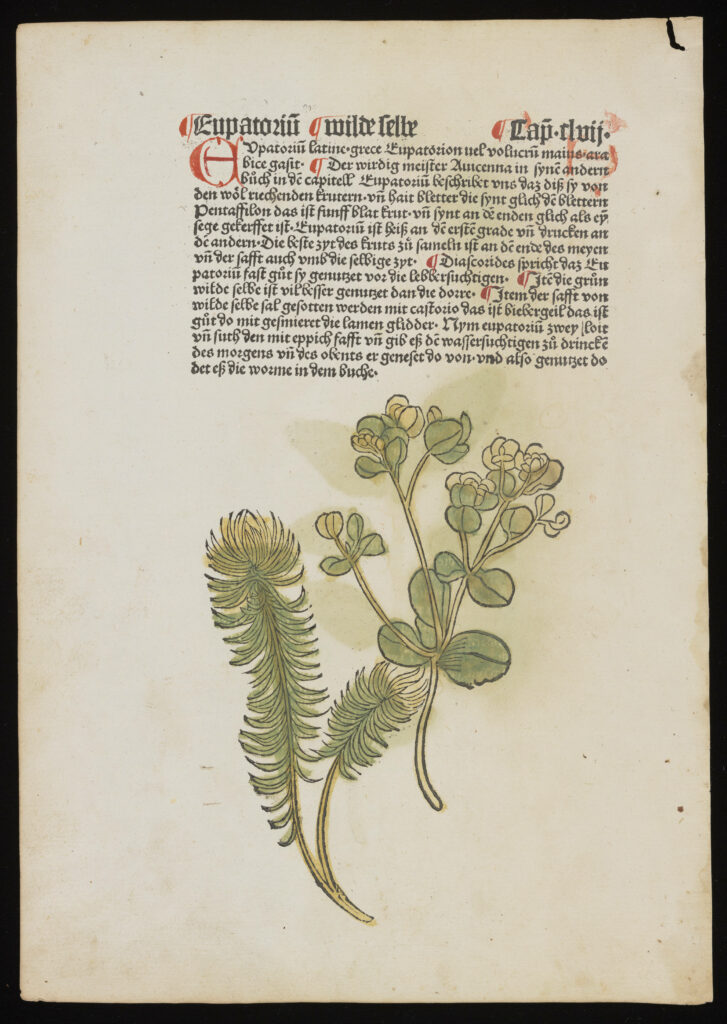

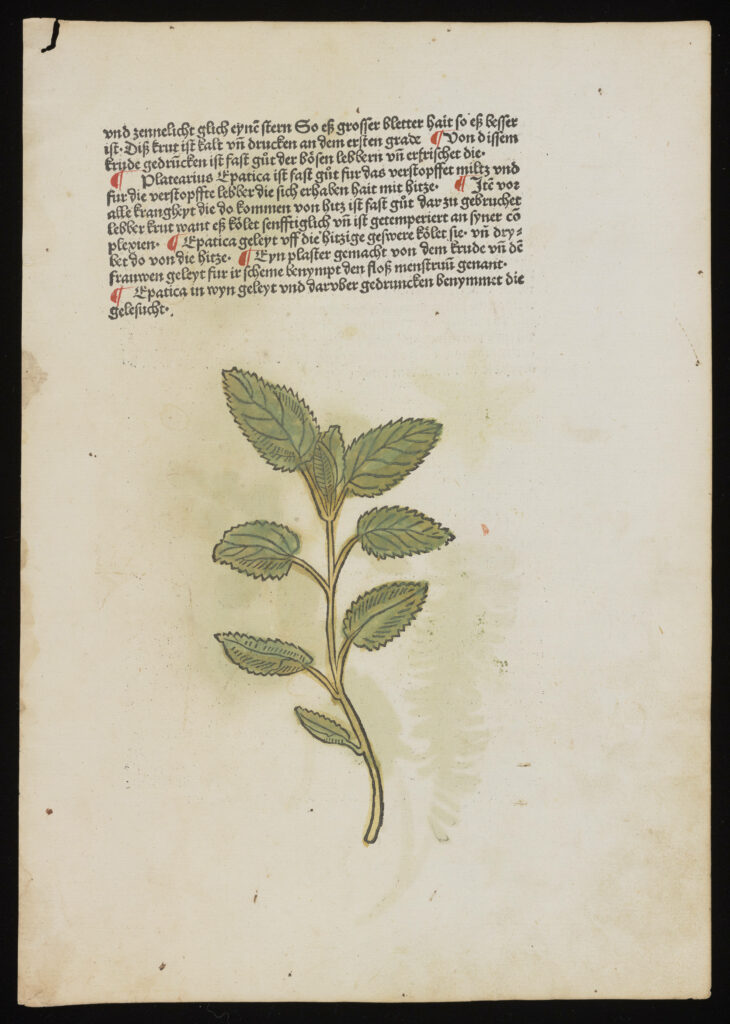

I found myself holding leaves (or individual pages) from manuscripts from the 1400s that were printed in Mainz by Gutenberg’s apprentice, Peter Schoffler, such as this:

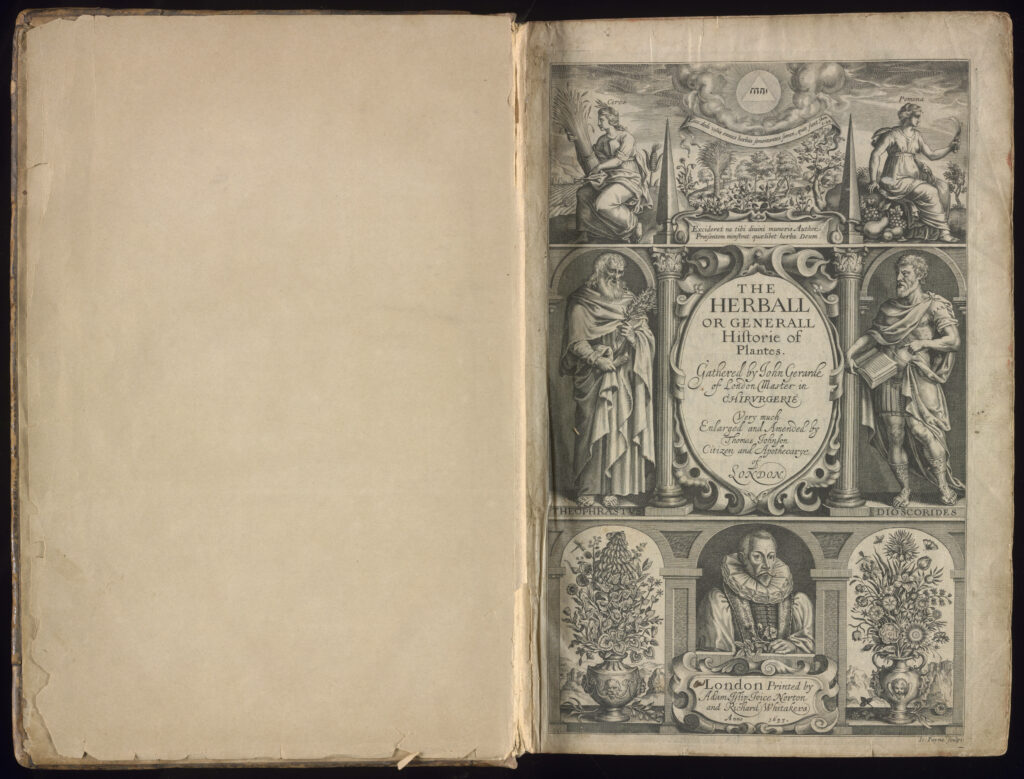

Or finding a copy of The Herball by John Gerard from 1633 that matched my fanciful ideas about what old books in a rare book vault would look like (the word “tome” is highly appropriate for this 1600+ page volume).

Or drooling over the stunning prints in the even more massive folio of Captain Cook’s Florilegium . The sheer variety of printing techniques, book shapes and sizes, and the wonder of holding leaves from books written by physicians to the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian the II, in this case, Pietro Mattioli’s commentary on Dioscorides work De Materia Medica , blew me away. Here was what I loved most about the printed page: tangible history.

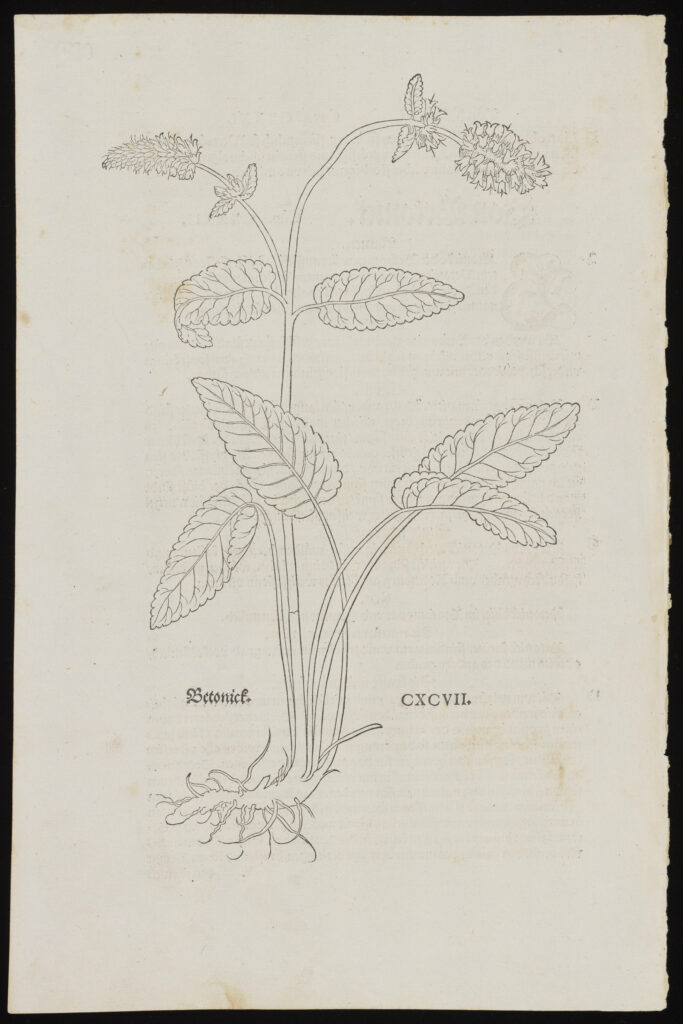

As I researched and dug up volumes and examples of botanical illustration, I marveled at how quickly image creation technologies were perfected. Simplistic woodcuts such as this:

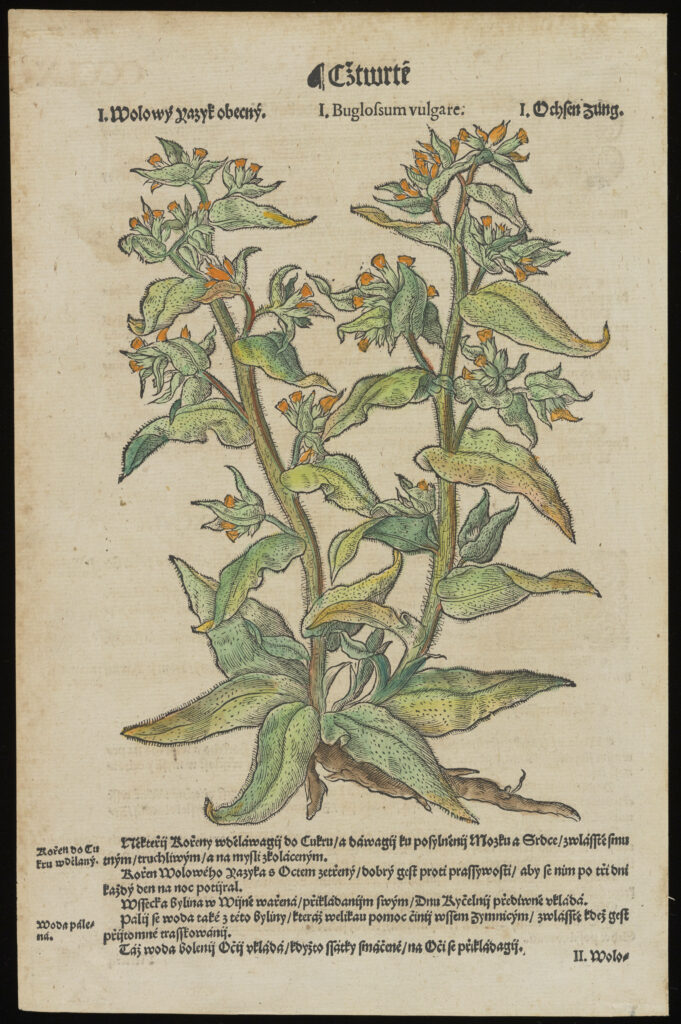

in earlier volumes gave way with remarkable speed to highly detailed, accurate representations of plants, like the following example, as authors insisted on more and more accuracy in the depictions.

This demand for true-to-life illustrations was not driven by an artistic desire for beauty, but for the absolute need of the author to ensure that plants were correctly identified so the herbals could be used as intended. These were practical choices, made to smooth the way for physicians, apothecaries, and others in the medical field to practice their important work.

As I selected images and texts for my physical and digital exhibits, I kept in mind the need to balance historical relevancy with the need to showcase examples of artistic and technical advancement. I selected images that fit into both categories as best I could. The physical exhibit was in many ways a less complicated creation process, as I simply had to research and select materials to be displayed. Working with Dr. Miriam Intrator, I learned the process of writing exhibit labels, which is a very different form of writing than I was used to, and how to treat the materials themselves so they would not be damaged by their display in the exhibit case.

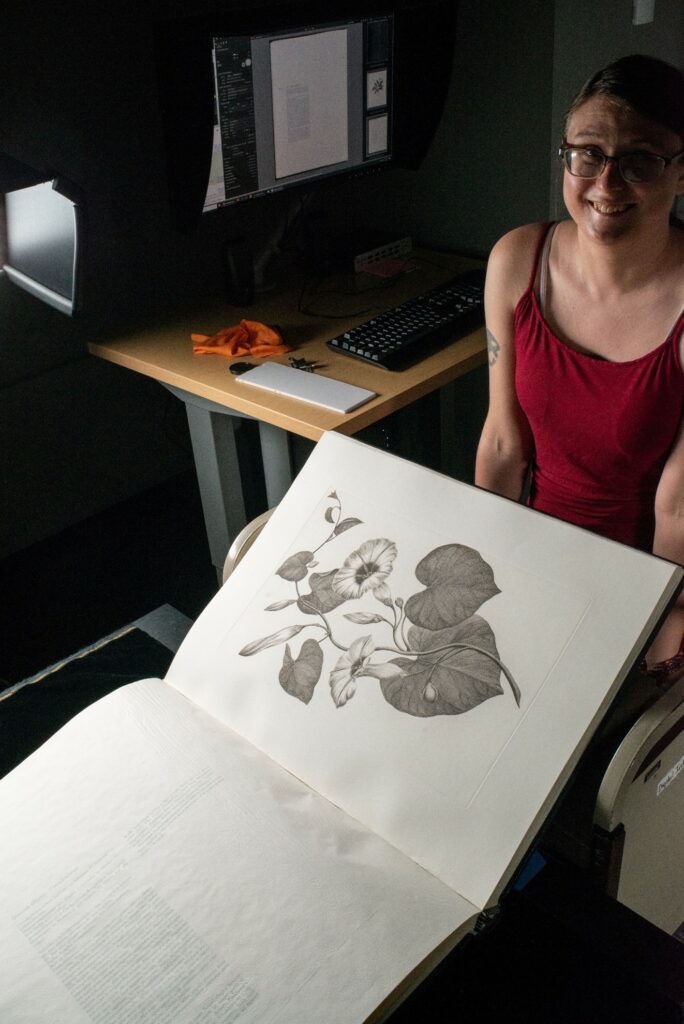

The digital exhibit had a much more complex creation process, as, after I researched and selected the items, I had to transform the physical into the digital. The leaves were already digitized, but the books were not. This led me to Digital Initiatives, where Erin Wilson, Digital Imaging Specialist and Lab Manager, worked with me to turn the physical texts into beautiful digital images. She ran the complex software and camera that took the pictures, while I adjusted the books to reveal the pages needed for the exhibit, a process called materials handling. Below is a behind-the-scenes glimpse of that process.

I also got to focus the lens of the special camera that allows for the digitization of materials in the collections to be shared with scholars all over the world, which was both fun and informative. Paired with this very enjoyable process was the need to fill out descriptive metadata sheets, another new experience for me. The final step of the digital exhibit was making it.

For this step, I worked with Laura Smith, Photo Archivist. She gave me invaluable help as I used Timeline JS and a Google spreadsheet to turn my collection of images, research, and ideas into a slideshow. I had never used a spreadsheet like this before, and as I filled out cells one by one with text and links to images, I learned bits of html and how to hammer my words into the format Timeline JS demanded. I learned how to write alt-text, how to resize images, and how to modify the look of the timeline itself. So many drafts were tweaked, tuned, and polished, until suddenly, it was a reality! This need for accuracy in image formatting paralleled the need for accuracy in the examples I was using in my exhibit-after all, I was using images in an educational manner, though not in the same way that the writers and artists had intended.

This need for accuracy for practical reasons continued well past the age of the herbal, when botanists and explorers came into contact with more new plants as global connections grew more numerous. The need to classify these plants, and to understand the science of botany, sparked the creation of teaching volumes, with realistic depictions of plants as much needed teaching aids. As exploration accelerated, journeys to other lands contained a strong scientific component, with naturalists and botanists taking samples and sending them back to be planted in botanical gardens, to be drawn, classified, and have the knowledge gained about them disseminated to the scientific and lay community.

Along with this sample taking was the harsh reality of colonial expansion, in which plants played an important role as well. So called “New World” crops reached Europe and Africa, and other crops, such as sugarcane, were seized and planted in new areas. Some of these plant exchanges had terrible results, while others did not. In the case of sugarcane, the plantation system arose to produce sugar and gave a horrible boost to the Atlantic Slave Trade . The image of the potato in John Gerards’ The Herball is a hint at this cross-continental exchange.

This is an art form that is still relevant today, with botanical illustrations continuing to flourish in the pages of current works on botany, naturalist studies of flora and fauna, and even in the pages of a magazine that began in 1779. Curtis’ Botanical Magazine , featured in the exhibit, was an early promoter of exotic blooms in the public consciousness and is still going strong today! The history of the art form has threads of compassion, in the case of herbals created to help heal, scientific advancement through instructional volumes and descriptions of new plants, and cross-cultural connection, with all its wonder and horror. Plants continue to be vital facets of our lives, as we still use them for medicine, for food, and for beauty. We still roam forests and plains, seeking new blooms to name and add to our understanding of botany. Botanical art is still an important method used to record these plants for humanities use and understanding of the world around us.

I would like to take a second to thank Dr. Intrator, Erin Wilson, and Laura Smith for all their invaluable help with this exhibit. They each shared their expertise, their patience, and their skills with me and helped make this exhibit possible. They taught me so much, and I enjoyed every minute of it!