By Maggie Bennink, ’24 BA in History & Classic Civilizations, Digital Initiatives Assistant

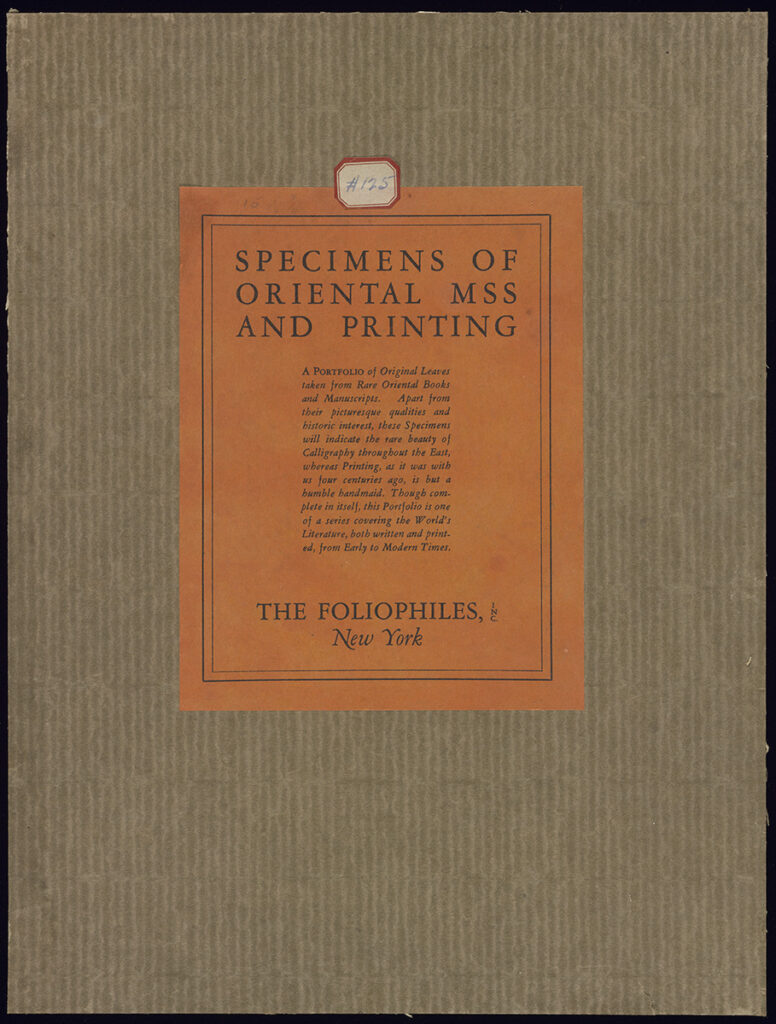

I was introduced to Pages From the Past over the 2023 spring semester, through an independent study led by Dr. Cory Crawford in the Classics Department. The items we looked at – a cylinder seal and a cuneiform tablet – are a part of a Pages From the Past collection we have in the Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections. Although the independent study was not geared towards researching these items and their origin, we were able to find more information about The Foliophiles Inc. and Pages From the Past collections as a whole.

“Pages From the Past” is the title of a series of collections released by The Foliophiles Inc. throughout the 1960s. Each collection, or “set,” exists on its own as individual and unique curations of materials. They are spread out across multiple institutions across North America as both whole sets and individual materials. Ohio University has five Foliophiles sets in our archives. I have been actively working on the digitization of these collections through the Digital Initiatives department at Alden Library.

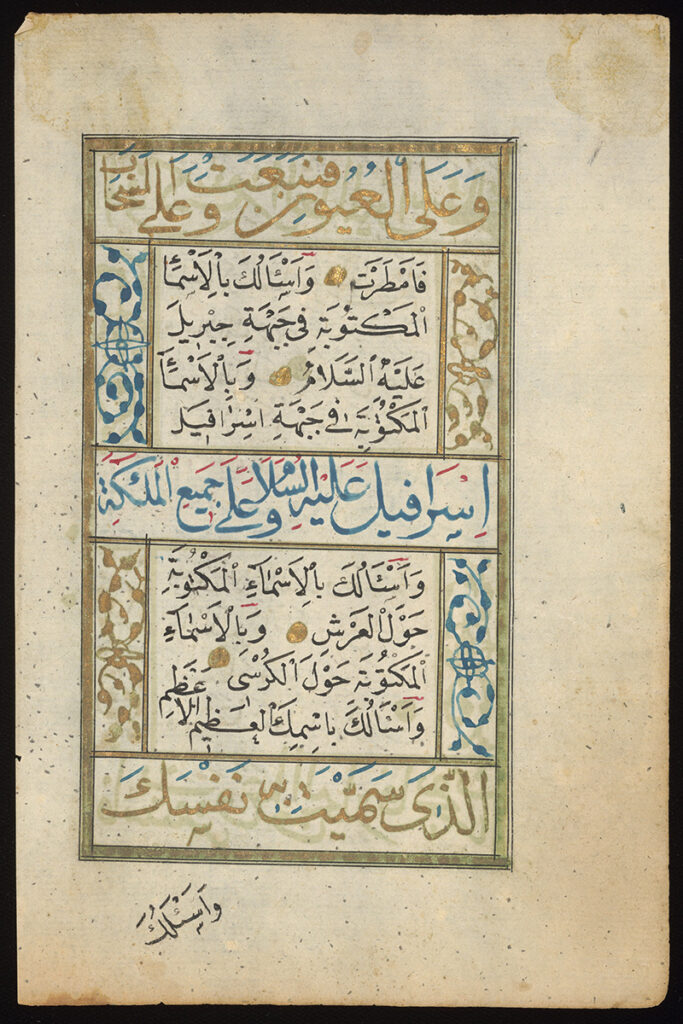

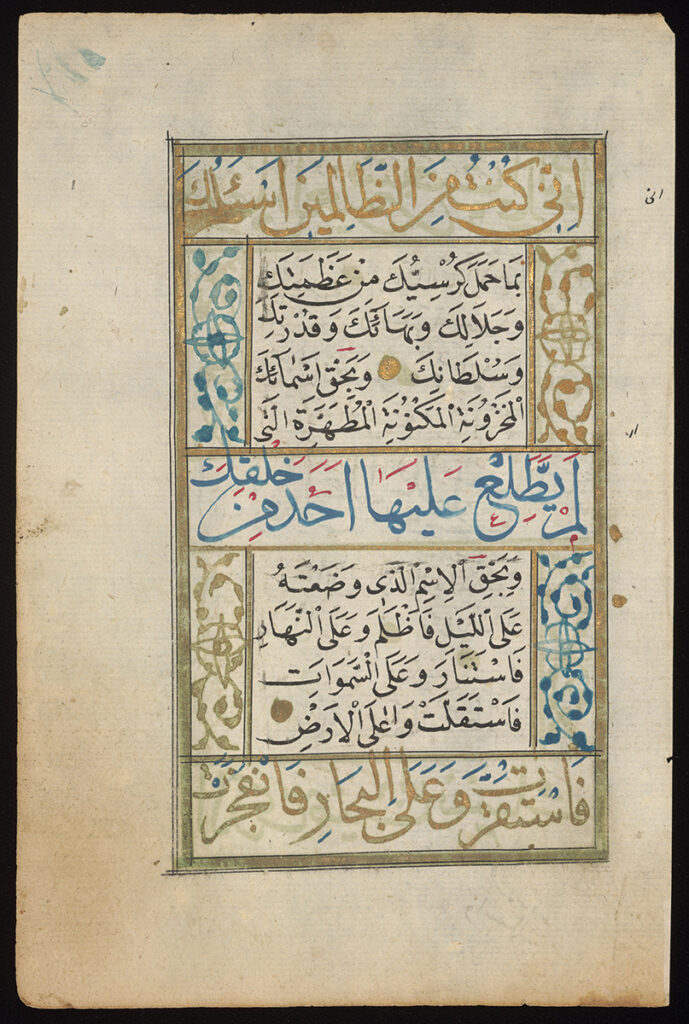

The collection I researched, described, and digitized this fall is Specimens of Eastern Manuscripts and Printing , originally titled “Specimens of Oriental Mss and Printing.” It contains 15 folders of materials, for a total of 24 items. They are grouped based on the type of item – for example, folder 2 contains both a printed and handwritten version of excerpts from a 17th century Arabic Koran (Qur’an) manuscript. We have not translated any of the leaves just yet, but that is one of the things we hope digitization will facilitate.

The aim of digitization is multi-faceted. Along with hoping the materials reach potential translators, we work to allow others (such as students, teachers, or anyone who is curious!) access to materials that they may not be given a chance to research in person. This requires high-quality images for review. The collection required some interesting techniques during digitization, as the materials in the collection are somewhat extraordinary.

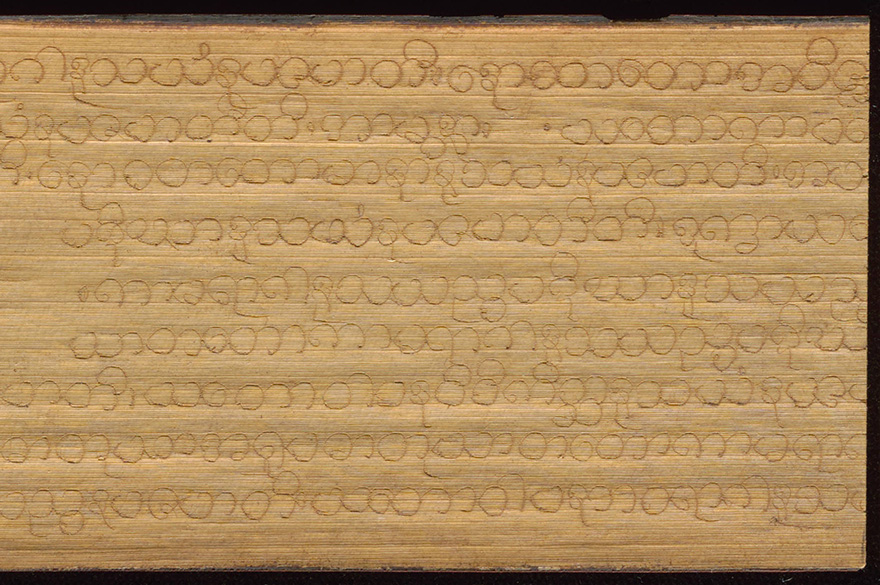

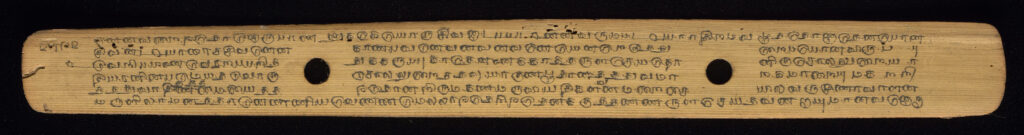

The last folder in the collection contains two rare and fragile items, which were quite thrilling to work with. They are both documents written on “taliput” (or talipot) palm leaves, in the language of Pāli, from the Indian subcontinent. This language was primarily recorded on palm leaves in the pre-modern era. These two leaves are supposedly from the 18th century, according to the collection notes. The palm leaves can be bound to each other through the holes in the center, which can be seen in the images below.

These items in our collection were hard to digitize because of how the letters are etched into the fibers of the leaves. The ink is flooded into tiny lines, which make s

the words three-dimensional. Because of this, our human eyes can detect what the text says just fine (with the help of a little manipulation of the angle at which we are viewing the leaves). However, our camera can really only see things from one direction, or two dimensions. So, when taking the images of the leaves, we had to get creative with the lighting in order to make the words as visible as possible.

Typically, we take photos of the front (recto) and back (verso) of manuscript folios. These materials are photographed as two-dimensional – think the pages from a book. But what if we want to convey a three-dimensional aspect of something typically captured in two dimensions? For example, take our Publishers’ Bindings collection. We captured the front and back covers straight on, but also included “three-quarters” shots to demonstrate that the books are physically dense objects rather than flat images on a screen. In the case of the taliput manuscripts, we weren’t able to stand them up in a way that could capture this multidimensional aspect, so we instead opted to alter the way the light was hitting the page. This was completely experimental, however, so there was a fair amount of trial and error.

In Digital Initiatives, our camera lab is set up so that we can lay the materials flat and photograph them from a bird’s eye view angle. There are two professional studio lights aimed at the central table from the left and right sides, positioned so there are no shadows cast over the image. Our first idea in capturing the three-dimensional writing on the palm leaves was to turn off each light individually, using the shadows to our advantage. The light was then only coming from one side of the table, otherwise known as raking light . We ended up turning off both lights individually, which resulted in two images with the light coming from opposite angles. While this did show off the shadows cast from the engravings, we weren’t happy about having two separate images to show off both sides. Plus, the side of the palm leaf that was further away from the light was almost completely cast in shadow.

So, we decided to try something else. Being very careful to mark where the light was before we moved it, we positioned one to the front side of the table. We couldn’t just rotate the leaf because it was too large to fit vertically in the camera frame, measuring in at 50.0 cm wide x 5.5 cm tall. With the light now raking across the long edge of the leaf, there were no parts of the leaf that were left in the dark. In order to capture the leaves at the highest quality, there was a lot of tweaking to be done with the camera settings as well. Once we figured that out, we had our final pictures!

This digitization technique was also used on the smaller taliput leaf in the same folder. The ink in this leaf was more visible, so we were less worried about getting the text to really pop .

There were other interesting manuscripts in the collection, including an illuminated page written in Arabic. The only information we have about this page’s origin is that it was created in the 16th century. The page has several interesting characteristics; it is illuminated, and it has rubrications and marginalia. Illumination means the page has been decorated with gold ink, whereas rubrication refers specifically to text in red or blue ink. Marginalia are notes and doodles in the margins of a manuscript. In order to get the gold ink to really stand out, we had to get creative with lighting once again. To capture the shimmer of the gold, we shone two flashlights directly over the leaf while we took the image to enhance the reflection on the gold leaf. This technique is common on gold and silver illuminations, as it allows more light from different angles to hit the paper and show the gleam of the metallic paint. It is interesting to see all of these characteristics on a manuscript leaf that is so small! (The manuscript is 10.1 cm wide x 15.5 cm tall)

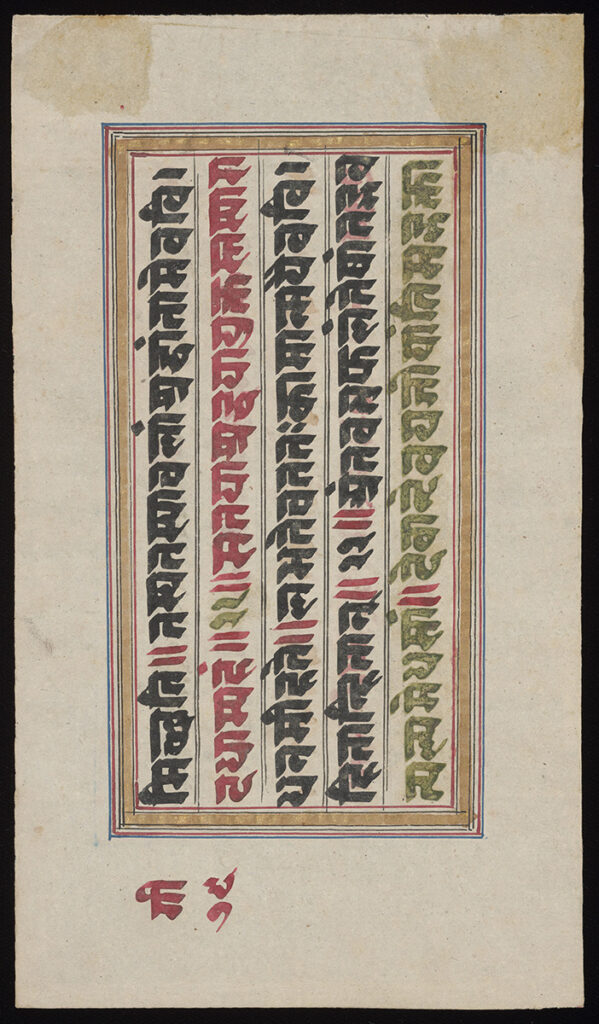

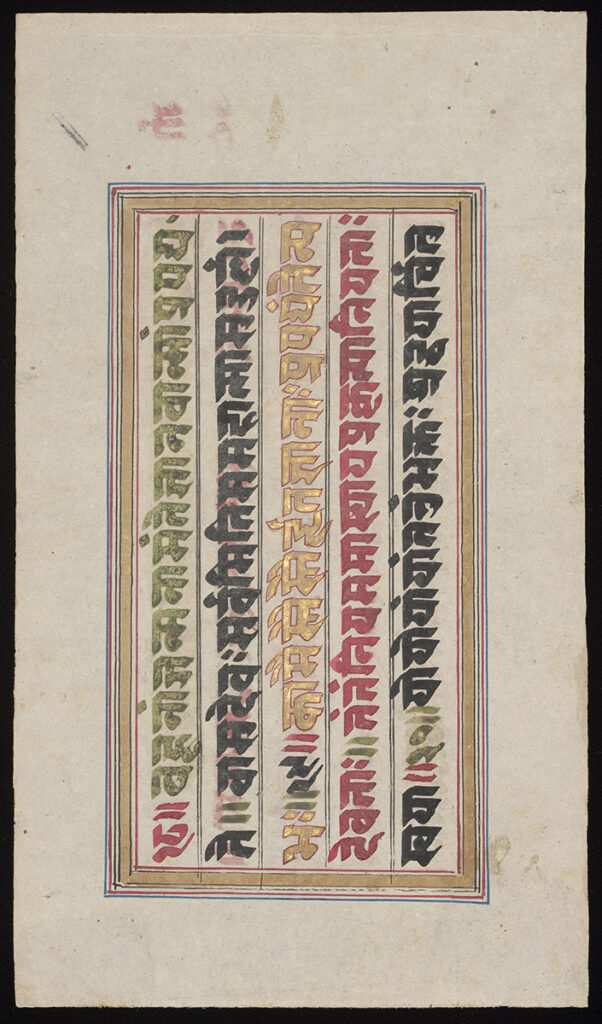

Another highlight from the collection is this Sanskrit manuscript leaf from the early 19th century. It has red and green rubrications – with some in the margins! – and is also illuminated. The text itself is from a book with selections of Indian mythopoetic legends. While we do not know for sure what this page is because we have not translated it, the collection notes state that it may be part of the Bhagavad Gita, a Hindu scripture from the epic Sanskrit poem Mahabharata .

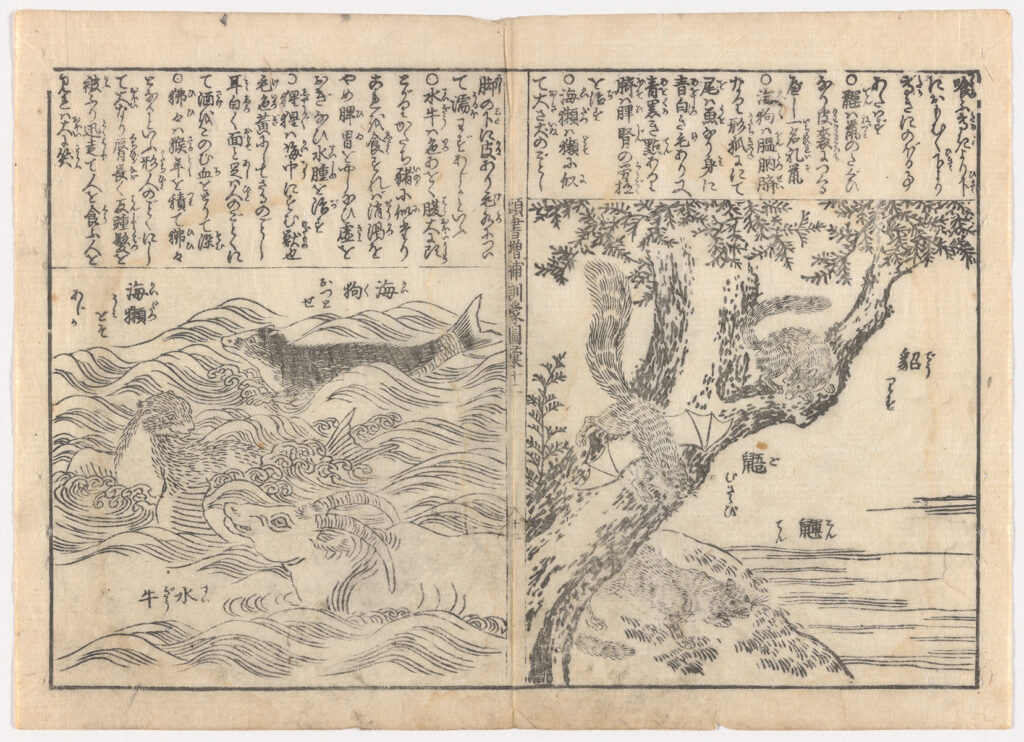

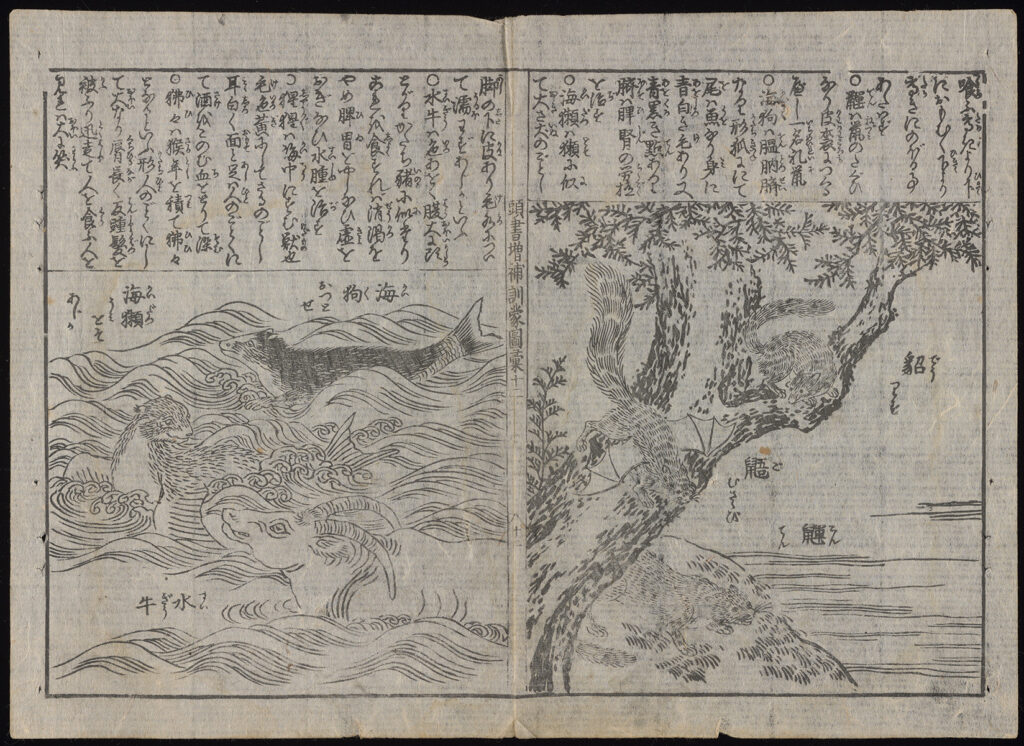

Last but not least is a very thin leaf from 1789. The page has a beautiful printed illustration on it, with Japanese text surrounding it. It was originally part of a children’s picture book, according to the collection notes. This was hard to digitize due to how thin the paper is. In order to improve the legibility of the text, we photographed the page against a white background. But, to show how thin the page is, we also captured it against both gray and black backgrounds.

I thoroughly enjoyed being able to handle these materials, and am grateful for the valuable experience working at Digital Initiatives has provided me. There are more Pages From the Past & Foliophiles, Inc. collections coming to the digital archives soon, so all you Alfred Stites fans, stay tuned!

For more information, and to view the full collection, visit Specimens of Eastern Manuscripts and Printing on OU’s Digital Archival Collections website.