By Di Galbraith ’25, History major, Globalization and Development minor, Fall 2023 Mahn Center intern

I have always been deeply fascinated by Appalachia. How the mountains came from the same range as the Scottish highlands, how communities were left behind and forgotten once modern technology developed, and how the people were stereotyped as dumb, rowdy, and ignorant. I grew up about two hours away from the region, but my family members, now long gone, called this land home for years. As my grandfather, who passed away in the 1980s, was the last of my family to live in the mountains before moving to Dayton, I know nothing about his life growing up in the mountains during the 1920s and 1930s. It was during this time the world forgot about Appalachia as industry and urbanization rapidly developed in more accessible areas.

I was so curious as to how a government could let its own people be so isolated and forgotten about, how many of the Appalachian communities came to this land, and why they got the stereotype they did. My curiosity about the mountains has followed me for years, compelling me to study their history and culture in depth. When I got the news that I would be creating the Appalachian Studies and Resources Guide during my Mahn internship, I was elated.

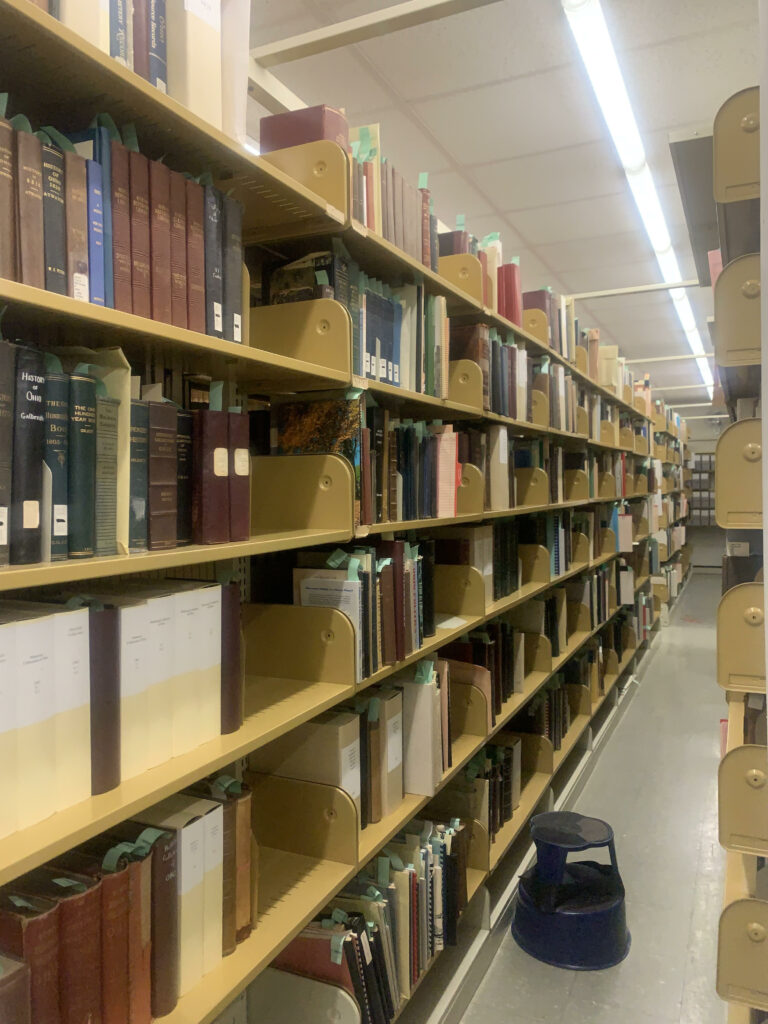

This project has been in the works for years, but with Ohio University sitting in the middle of Appalachian Ohio, there was an incredible and growing amount of material to sort through. Initially, it was overwhelming, but I felt confident after receiving guidance from Dr. Miriam Intrator. I began by meeting with each collection curator head, Bill Kimok, Laura Smith, and Greta Suiter, to see what they believed would make a good fit into the guide. Many of the items were Ohio and Ohio University-centric, but that was to be expected. I then perused all the material they had suggested to me. At the same time, I searched through the ALICE catalog, digital archives, and the rare books vault for anything and everything on Appalachia.

For each item I looked over, I added it to a spreadsheet. I had not used a spreadsheet since my sophomore year of high school, so it took a bit of relearning. I separated each collection and sorted each item by relevance and content: history, art, activism, industry, writings, and genealogy. By the time I had finished, I had over 100 entries on the spreadsheet. I had a rough draft of a guide created and began moving books over before quickly realizing I needed to narrow down my list and create more concise pages within the guide. After meeting with Dr. Intrator, we came up with a basic structure for the final guide, and I began to work on the final draft. I narrowed down the entries to roughly five resources per topic. I allowed a little bit more resources for the industry page as we had so many collections centered around the Appalachian industry. I knew that many people would be using this guide to help with genealogical research, so I tried to find as much relevant and well-rounded information as I could.

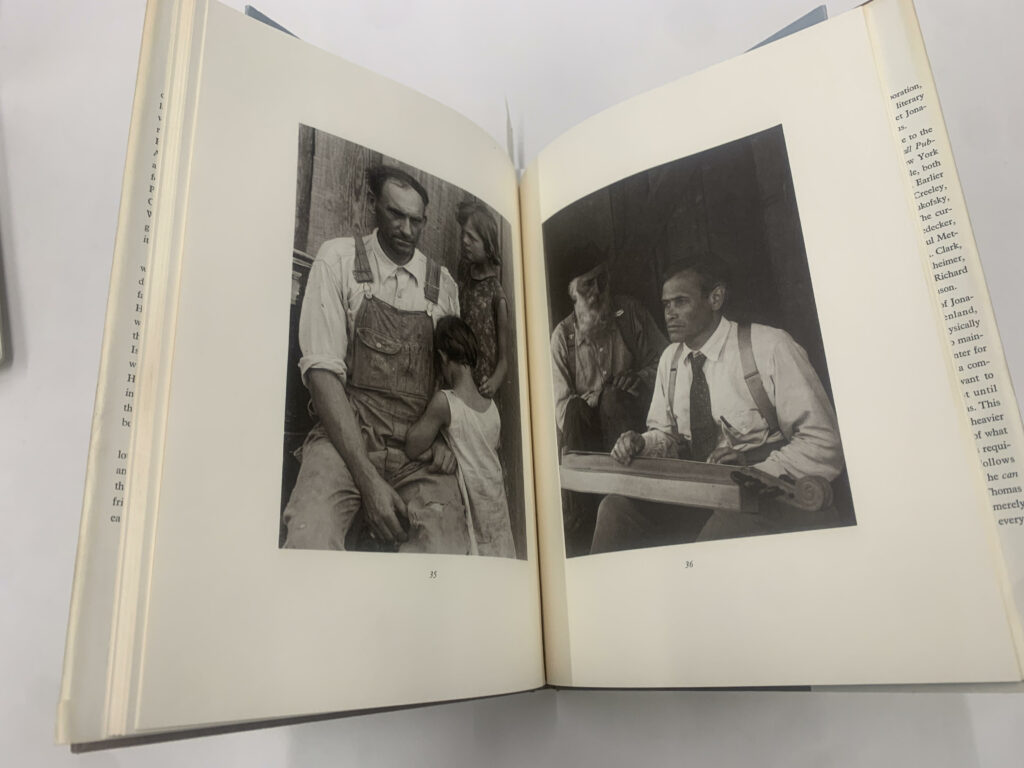

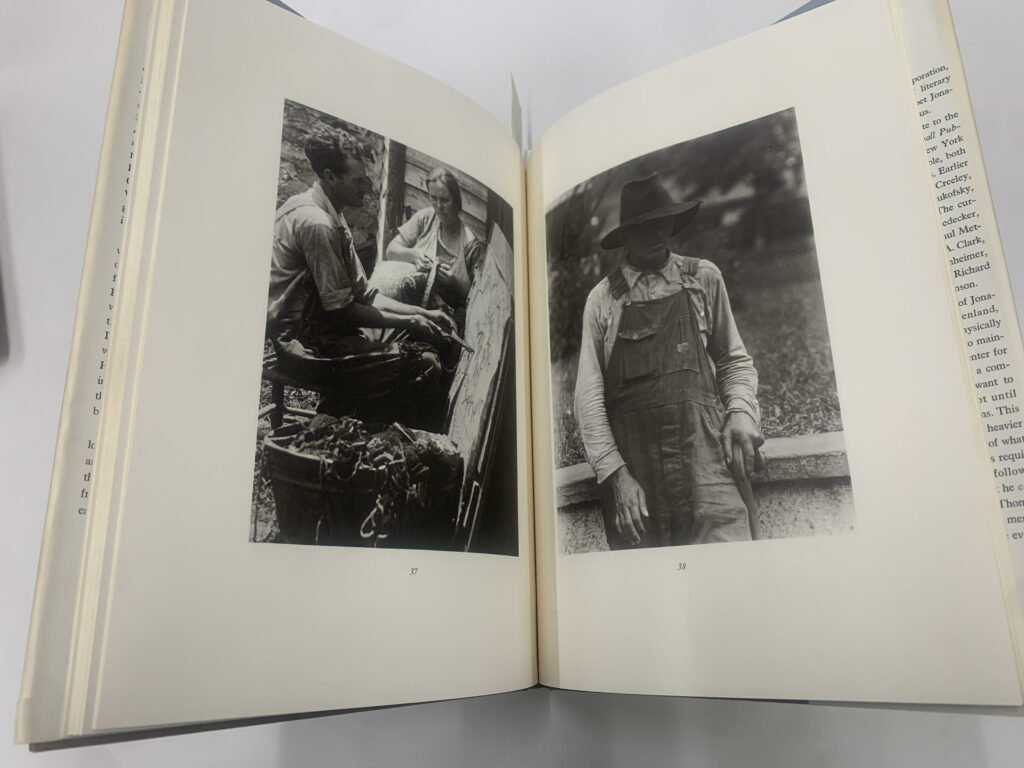

Two photographic spreads from The Appalachian Photographs of Doris Ulmann (1971).

Narrowing down the entries was by far the hardest task at hand. Each entry was captivating in its own way. Some were easier to rule out as they were not Appalachian-centric or were out of date, but for the most part, dozens of resources could have been added. One helpful realization was that over twenty of the rare books on niche Appalachian topics were published by Ohio University Press . This allowed me to place a blurb in the Other OHIO library resources section of the guide about OU Press and its many books on everything Appalachian. I spent weeks re-looking and comparing and contrasting every entry before I finally narrowed it down. For the chosen few, I swiftly added them to the guide, writing a brief but informative blurb about each. Then, I utilized the digital archives and photo collections to find pictures to accompany each page to help illustrate the information. This also allowed for the guide to be more visually interesting and to show off different collections.

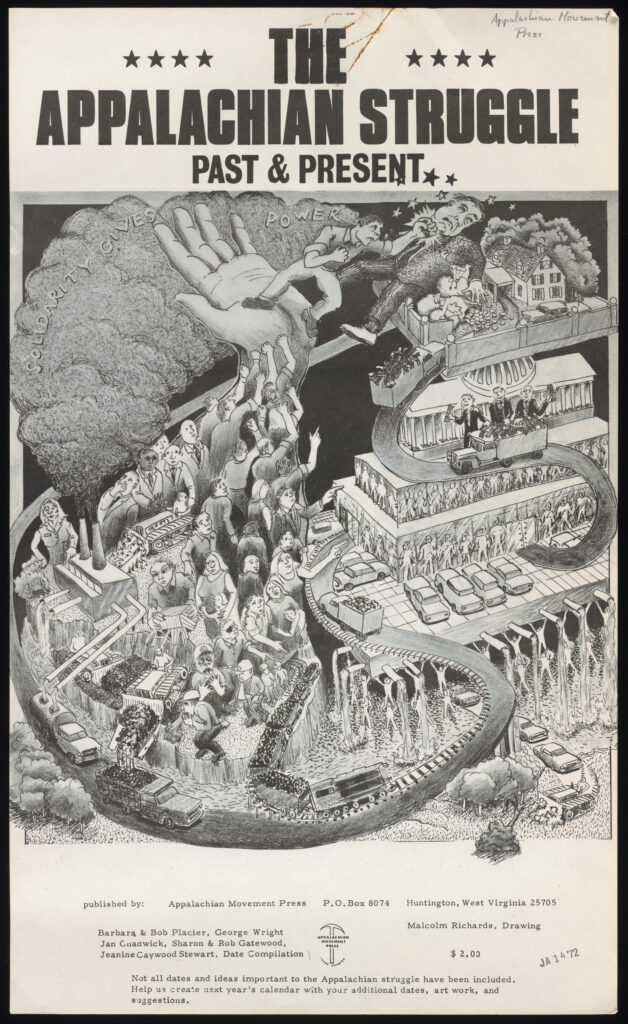

The purpose and creation of this guide is to help anyone who wishes to educate themselves on Appalachia, and southeastern Ohio in particular. With the tremendous amount of government and industrial records, descendants of Appalachian families could potentially find information on their ancestors. Where they worked, who they married, where they lived, when they died, and where they were buried. For those interested in labor unions in Appalachia, there is a whole collection dedicated to them. For those curious about how Appalachia has been portrayed by its citizens, there are the art and the writings pages. The activism page allows people to educate themselves on minority communities and the fight for equality within the region. Finally, for those who do not know where to start, there’s the history page. The history page has resources for a more general history and information on Appalachia. If one has an extremely niche topic they wish to learn more about, Ohio University Press has dozens of books dedicated to everything in Appalachia. There are also the Mahn Center Reference Room vertical files on Southeast Ohio and Ohio counties that have first-hand accounts and newspaper articles on everything from organizations, folklore, natural disasters, mining, and more.

Over the last semester, I have learned more about my aspirations and interests than I have ever before. I knew that I wanted to go into history, but not quite what. Seeing the work of everyone in the Mahn Center solidified my desire to go into a career in archiving or preserving artifacts. This experience has also solidified my interest in Appalachia and its development. Seeing so many accounts of feeling abandoned by the world and of the effects of growing up in isolation has a hold on my heart. The fight against mountain-top mining and destructive environmental practices is never taken seriously, as those who are most affected are stereotyped as lesser and dumber. If this guide could help just one person educate themselves on anything Appalachian, I would be eternally happy. As long as I live, Appalachia and the fight to protect its culture and traditions will be with me.