By Emma Snyder-Lovera, BSJ, BSC ’26, for JOUR 4310 Gender, Race, and Class in Journalism and Mass Media with Victoria LaPoe, Spring 2025

During the spring 2025 semester, the staff of the Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections worked intensively with Victoria La Poe’s JOUR 4130 class, Gender, Race, and Class in Journalism and Mass Media. The students explored, selected, and researched materials from the collections, then worked in small groups to prepare presentations. The students had the option to then expand their research into a blog post like this one for their final project.

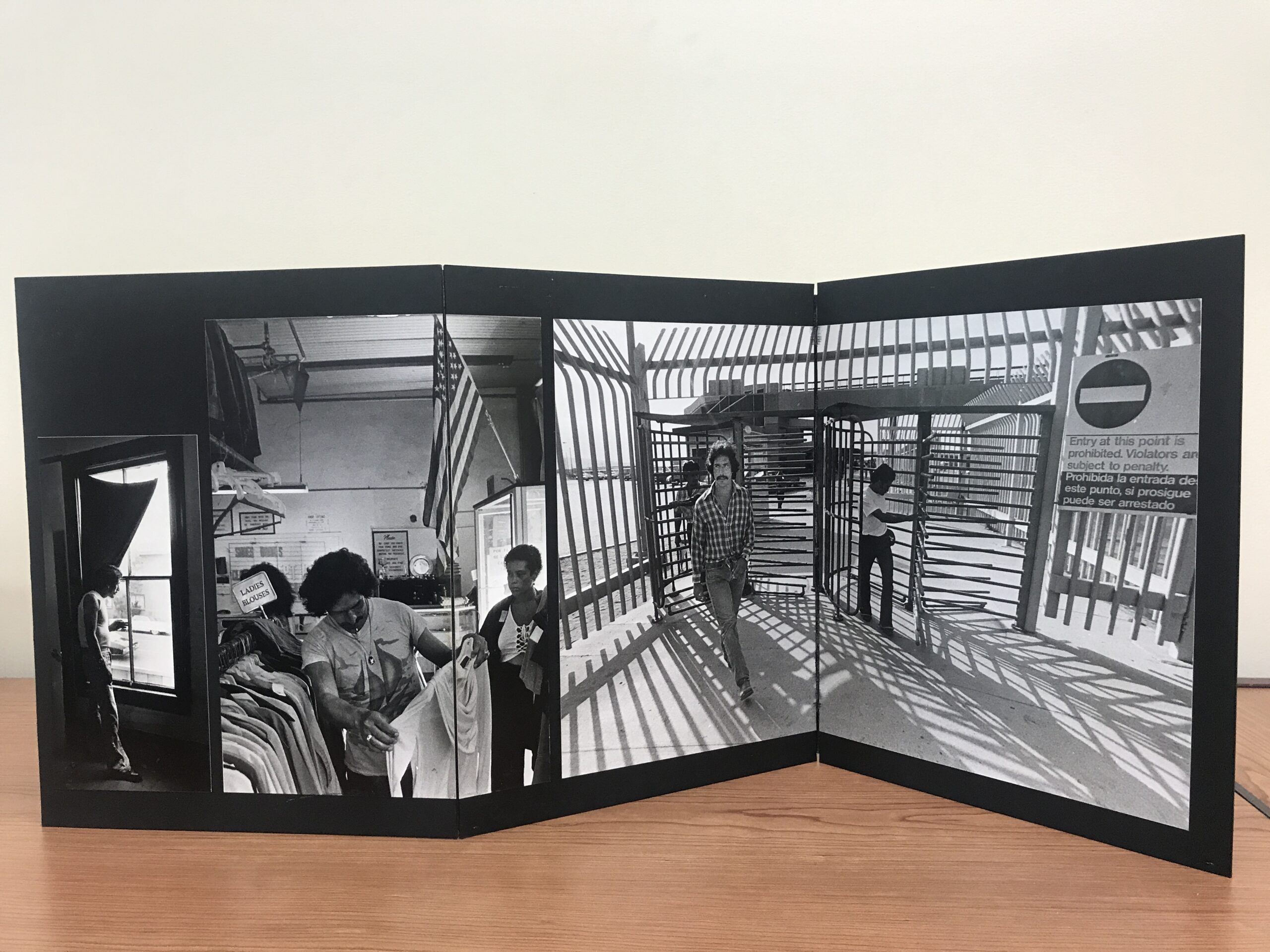

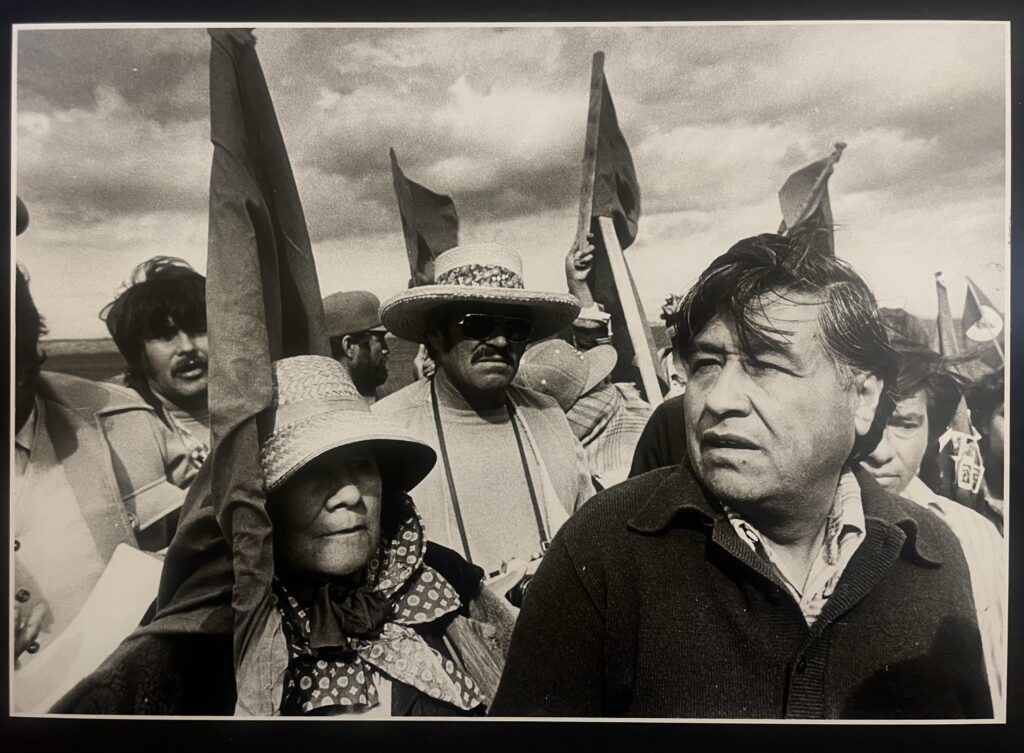

In the Hwa-Wei Lee Library Annex , there are a series of captivating photographs in the Documentary Photography Archive that depict the unvarnished experiences of Mexican immigrants. The Leonard Vaughn-Lahman Photograph Collection includes a series of photos titled “United States & Return to Mexico.” The stories of Gavino Hernandez and several other immigrants traveling from Mexico to California are told through photos and captions in a brilliantly intimate way. These photos were taken in 1980. One caption reads:

“Gavino came to California at the onset of the 1980 recession. Since most have to claim to welfare or unemployment insurance, they are the first to be laid off and last to be re-hired. After a marginal 3-month stay in San Diego, Gavino bought some used clothing for his family and returned to Mexico, more in debt than when he left. Re-entering Mexico at Tijuana, Gavino eyes Mexican customs agents, yet another source of trouble and exploitation. His savings and purchases well hidden, he begins his journey home — but he will return. As it does countless others, economic necessity will force him to do so. And so, the cycle continues.” ( “United States & Return to Mexico – 4th in series of 4, 1981.”)

Many themes captured in Vaughn-Lahman’s photographs—hardship, resilience, family separation, and the pursuit of opportunity—are still central to immigrant experiences today. The difference lies in how these stories are framed.

While Vaughn-Lahman’s images offer a deeply human and empathetic portrayal, modern media coverage often reduces immigrant narratives to statistics, policy debates, or political talking points. By engaging with these historical photographs, one considers how visual storytelling can foster empathy and understanding and how journalists today can learn from the care and intention behind Vaughn-Lahman’s work. In an era of rapid news cycles and polarized discourse, returning to these personal, nuanced portraits reminds us that immigration is not just a headline—it’s a human story.

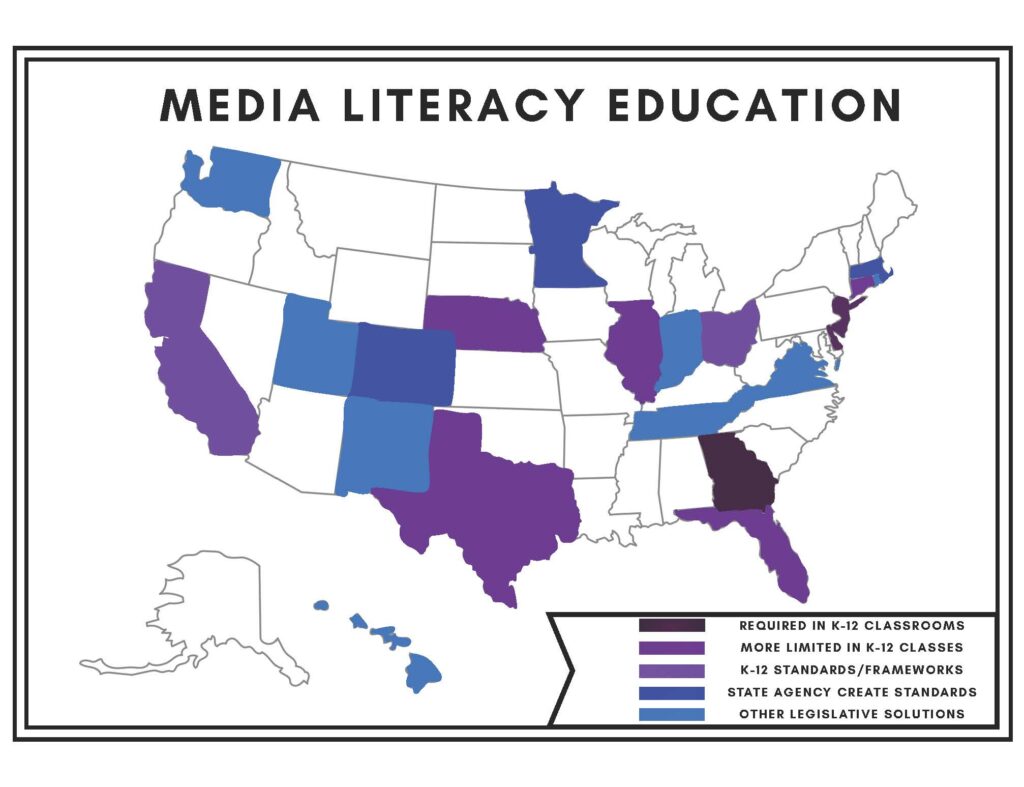

Dr. Pedro Cabrera is an educator of journalism at the University of Texas at San Antonio and San Antonio College. He is also an Academic At-Large for the National Association of Hispanic Journalists. When it comes to the stories of immigrants in today’s news cycle, he believes the impact largely relies on the audience’s media literacy skills. Only 18 states have some legislative solutions in place for addressing media literacy education, three of which require education in K-12 schools.

“It’s really difficult for the news media to do good reporting when the viewer doesn’t want to receive it,” says Cabrera.

Media literacy is essential for understanding how immigrants’ stories are constructed, framed, and disseminated. It involves more than just consuming information—it means questioning who is telling the story, what sources journalists are using, what language and images they choose, and what perspectives they include or exclude. When it comes to immigration, these questions become especially urgent. Immigrant communities are often portrayed through narrow lenses, as threats, victims, or economic burdens, rather than as complex individuals with families, aspirations and diverse experiences.

Understanding the impact of framing and priming is key when engaging with media centered around immigrant stories . A photo of a crowded border facility can evoke fear or empathy depending on the headline that accompanies it. Similarly, the words journalists use, “illegal” vs. “undocumented,” for example, carry political and emotional weight. Media literacy helps audiences recognize how such language influences public opinion. It also encourages viewers to seek out underrepresented voices, such as immigrants’ accounts or independent journalism that challenges mainstream narratives.

Examining the Len Vaughn-Lahman photographs, media literacy also means recognizing how past depictions of immigration can both inform and contrast with present-day coverage. The photographs provide a strikingly personal and empathetic portrayal of migrants traveling between Mexico and the United States in 1980. These images challenge viewers to consider the individuals behind the headlines. Vaughn-Lahman’s captions are raw, honest depictions of immigrant life – but the photographs make viewers see and believe the words they are reading. Older visual narratives invite some reflection: What is changing in how immigration is reported? What stereotypes persist? What gets lost in today’s political landscape? By comparing historical materials with current media, audiences can develop a deeper, more nuanced understanding of immigration and their role as informed media consumers.

In today’s political landscape, media prejudice towards Mexican migrants has contributed to the perception of the Latino community as a threat and a danger. Immigrant communities are often portrayed negatively and in relation to crime, but even when portrayed positively, they remain an underrepresented group in media. This problem of immigrant representation in media will only continue to move to the forefront of the United States’ cultural zeitgeist as deportation arrests increase. If audiences practice media literacy skills, it is more likely that Latino stories will be given positive representation and be received more accurately.

If any journalist is reporting on Hispanic or immigrant stories, the National Association of Hispanic Journalists provides a Cultural Competence Handbook and guidelines for reporting on immigration raids . The NAHJ is working to ensure that these stories stay protected and told with care.

References

Cultural Competence Handbook. (n.d.). https://nahj.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/NAHJ-Cultural-Competence-Handbook.pdf

Famulari, U. (2020). Framing the Trump Administration’s “Zero Tolerance” Policy: A Quantitative Content Analysis of News Stories and Visuals in US News Websites. Journalism Studies, 21(16), 2267–2284. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2020.1832141

Guidelines for Reporting on Immigration Raids. National Association of Hispanic Journalists. (n.d.). https://nahj.org/immigration-guidelines/

Leonard Vaughn-Lahman Photograph Collection. Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections, Ohio University Libraries, Athens, Ohio. https://archivesspace.ohio.edu/repositories/2/resources/401

Media Literacy defined. NAMLE. (2025, January 24). https://namle.org/resources/media-literacy-defined/

Mendelsohn, J., Budak, C., & Jurgens, D. (2021, April 13). Modeling Framing in Immigration Discourse on Social Media. arxiv.org. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2104.06443

Scheufele, D. A., & Tewksbury, D. (2007). Framing, Agenda Setting, and Priming: The Evolution of Three Media Effects Models. Journal of Communication, 57, 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00326.x