- News & information

- About

- History

- George V. Voinovich

- George V. Voinovich Collection

- Calendar

- How to Find Us

- News

- Archives

- Photojournalism Fellowship Project

- Photo Essays

- Current Fellow

- Previous Fellows

- Reports and Publications

- Archives

- Students

- Prospective

- Center for Entrepreneurship

- Environmental Studies

- HTC/Voinovich School Scholars

- Master of Public Administration

- Current

- HTC/Voinovich School Scholars

- Center for Entrepreneurship

- Environmental Studies

- Master of Public Administration

- Alumni

- Contact

- School Leadership

- Strategic Partners Alliance

- Ohio University Public Affairs Advisory Committee

- Ohio University Public Affairs Advisory Committee

- Faculty and Fellows

- Faculty

- Visiting Professors

- Voinovich Fellows

- Professional Staff

| Lawrence M. Witmer,

PhD

|

|

Evolution of the sense of smell in dinosaurs and birds |

Common Language Summary

Common Language Summary

Evolution

of olfaction across the dinosaurian transition to birds.

Everyone knows birds aren’t exactly bloodhounds.

The party line has been that

the

evolution of

flight in birds favored vision and balance over olfaction, and

so the sense of smell was reduced. A new study overturns that

perception, showing that as birds evolved from theropod

dinosaurs their sense of smell was maintained and actually

increased in basal birds. The olfactory bulbs of the brain,

where information on odors is processed, were measured in 157

species of non-avian dinosaurs, fossil birds, and modern-day

birds. For many of the fossil species, CT scanning provided the

first-ever glimpse into brain and olfactory bulb structure.

Rather than diminishing, the olfactory bulbs of the earliest

birds were still basically dinosaur-sized, and even increased in

relative size among early birds, including in the earliest

members of the radiation of modern-day (neornithine) birds. As a

result, the sense of smell remained very important to early

birds, even as they were simultaneously honing other parts of

their “flight computer,” and early birds may have used odors to

a much greater extent in navigation and foraging than do most

birds today. Another key finding is the unexpected importance of

smell for non-avian theropods. Many dinosaur species that we

usually regard as having used mostly vision, such as Velociraptor

, Bambiraptor

and Troodon

, almost

certainly also relied on smell. So, how did this notion of birds

having a weak olfactory sense become dogma? As it turns out, the

birds with the smallest olfactory bulbs are the ones we see

every day—the perching birds (crows, finches) at our feeders and

the parrots in our birdcages. It also may be no coincidence that

these are also the cleverest birds, suggesting that enhanced

smarts may decrease the need for a powerful sniffer.

• Download a PDF of the published article, along with the Supplementary Information:

Zelenitsky, D. K., F. Therrien, R. C. Ridgely, A. R. McGee, and L. M. Witmer. 2011. Evolution of olfaction in non-avian theropod dinosaurs and birds. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 278:3625–3634 .

• François Therrien's Royal Tyrrell Museum site

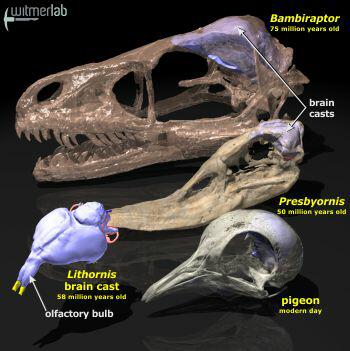

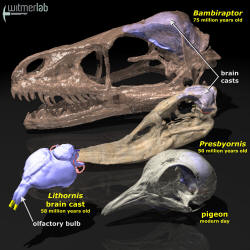

Evolution in birds of the olfactory bulb, the part of the brain where smell information is processed, passing from a dinosaur ( Bambiraptor ) through early birds ( Lithornis , Presbyornis ) to a modern-day bird (pigeon). Courtesy of WitmerLab at Ohio University.

Evolution in birds of the olfactory bulb, the part of the brain where smell information is processed, passing from a dinosaur ( Bambiraptor , top ) through early birds ( Lithornis , left; Presbyornis, middle right ) to a modern-day bird (pigeon, bottom right). Courtesy of WitmerLab at Ohio University.

• Download a 19 MB QuickTime version (HD: 1920x1080)

• Download a 7 MB QuickTime version (1280x720)

• Download a 4 MB QuickTime version (853x480)

The dinosaur Bambiraptor in a turkey vulture's colours. Bambiraptor had a keen sniffer similar to that of a modern-day turkey vulture. Courtesy of Julius Csotonyi. Restrictions: use for web-based releases only, otherwise contact artist [julius.csotonyi@gmail.com ]

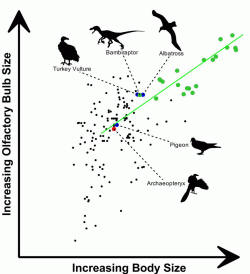

Graph of olfactory bulb size and body size of individual bird (black symbols) and dinosaur (green symbols) species. Similarities in olfactory bulb size and body size between species, as illustrated by the dinosaur Bambiraptor , the turkey vulture, and the albatross, suggest a comparable sense of smell. Courtesy of Darla Zelenitsky

Birds inherited strong sense of smell from dinosaurs

Study provides new details on evolution of smell, from dinosaurs

to modern-day birds

ATHENS, Ohio (April 13, 2011) – Birds are known more for their senses of vision and hearing than smell, but new research suggests that millions of years ago, the winged critters also boasted a better sense for scents.

A study published today by scientists at the University of Calgary, the Royal Tyrrell Museum and the Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine tested the long-standing view that during the evolution from dinosaurs to birds, the sense of smell declined as birds developed heightened senses of vision, hearing and balance for flight. The team compared the olfactory bulbs in the brains of 157 species of dinosaurs and ancient and modern-day birds.

The findings, published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B , dispute that theory. The scientists discovered that the sense of smell actually increased in early bird evolution, peaking millions of years ago during a time when the ancestors of modern-day birds competed with dinosaurs and more ancient branches of the bird family.

“ I t was previously believed that birds were so busy developing vision, balance and coordination for flight that their sense of smell was scaled way back,” said Darla Zelenitsky, assistant professor of paleontology at the University of Calgary and lead author of the research. “Surprisingly, our research shows that the sense of smell actually improved during dinosaur-bird evolution, like vision and balance.”

In an effort to conduct the most detailed study to date on the evolution of sense of smell, the research team made CT scans of dinosaurs and extinct bird skulls to reconstruct their brains. The scientists used the scans to determine the size of the creatures’ olfactory bulbs, a part of the brain involved in the sense of smell. Among modern-day birds and mammals, larger bulbs correspond to a heightened sense of smell.

“Of course the actual brain tissue is long gone from the fossil skulls,” said study co-author Lawrence Witmer, Chang Professor of Paleontology at the Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, “but we can use CT scanning to visualize the cavity that the brain once occupied and then generate 3D computer renderings of the olfactory bulbs and other brain parts.”

The study revealed details of how birds inherited their sense of smell from dinosaurs.

“The oldest known bird, Archaeopteryx , inherited its sense of smell from small meat-eating dinosaurs about 150 million years ago,” said François Therrien, curator of dinosaur palaeoecology at the Royal Tyrrell Museum and co-author of the study. “Later, around 95 million years ago, the ancestor of all modern birds evolved even better olfactory capabilities.”

How well did dinosaurs smell, especially compared to modern animals? Although scientists haven’t been able to make an exhaustive comparison, Witmer noted that the ancient beasts most likely exhibited a range of olfactory abilities. T. rex had large olfactory bulbs, which probably aided the creature in tracking prey, finding carcasses and possibly even territorial behavior, while a sense of smell was probably less important to dinosaurs such as Triceratops , he said.

The team was able to make some direct comparisons between the ancient and modern-day animals under study. Archaeopteryx , for example, had a sense of smell similar to pigeons, which rely on odors for a number of behaviors.

“Turkey vultures and albatrosses are birds well known for their keen sense of smell, which they use to search for food or navigate over large areas,” says Zelenitsky. “Our discovery that small Velociraptor -like dinosaurs, like Bambiraptor , had a sense of smell as developed as turkey vultures and albatrosses suggests that smell may have played an important role while these dinosaurs hunted for food.”

If early birds had such powerful sniffers, why do birds have a reputation for a poor sense of smell? Witmer explained that the new study confirms that the most common birds that humans encounter today—the backyard perching birds such as crows and finches, as well as pet parrots—indeed have smaller olfactory bulbs and weaker senses of smell. It may be no coincidence that the latter are also the cleverest birds, suggesting that their enhanced smarts may have decreased the need for a strong sniffer, he said.

Other authors on the article include Amanda McGee, a graduate student at the University of Calgary, and Ryan Ridgely, a research associate in the WitmerLab at Ohio University. The research was funded by grants to Zelenitsky from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and to Witmer and Ridgely from the U.S. National Science Foundation.

Editors: Related images and an animation created by the WitmerLab can be downloaded here: bird_olfaction_ProcB.htm .

Contacts:

1. USA (Eastern time zone): Lawrence Witmer, (740) 593-9489 and

(740) 591-7712,

witmerL@ohio.edu

.

2. Canada (Mountain time zone): Darla Zelenitsky, (403) 804-4998, and (403) 220-8016; dkzeleni@ucalgary.ca ; François Therrien, (587) 777-4548, francois.therrien@gov.ab.ca .

This project was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation .

Contact Information:

(740) 593–9381 | Building 21, The Ridges

Ohio University Contact Information:

Ohio University | Athens OH 45701 | 740.593.1000 ADA Compliance | © 2018 Ohio University . All rights reserved.